BANFF – A wolf from the Bow Valley pack made an epic 500-kilometre journey to Montana in the U.S. over the course of a week where it was shot and killed by a hunter.

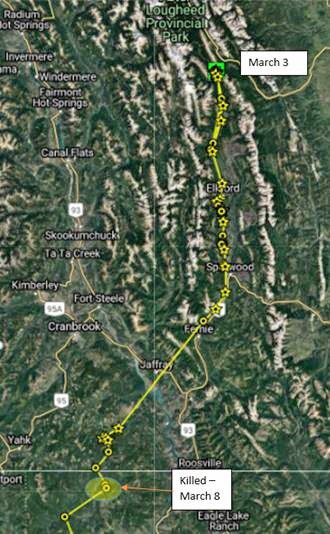

On Feb. 28, the GPS-collared sub-adult male wolf left his home range in Banff National Park. He travelled south along Elk Valley, passing north of Fernie, B.C., and across the U.S. border into Montana where he was killed on March 8.

Parks Canada initially reported the animal, known as No. 2001, was shot by a rancher, but later confirmed it was legally killed by a hunter with a tag to hunt wolves.

Bill Hunt, resource conservation manager for Banff National Park, said it’s an unfortunate ending for wolf No. 2001, but his 500-km trek also suggests some level of connectivity has been maintained between the two countries.

“While this was an amazing dispersal, sometimes wolves don’t even make it out of the park, and certainly when they do, they have a much higher mortality rate,” he said.

“It’s fairly poignant that the sibling of this animal died in Banff on the railway tracks just a few months ago.”

The Banff wildlife team shared wolf 2001’s movements with respective land managers and biologists as he travelled outside the national park boundary onto provincial lands.

Parks Canada staff had been tracking this almost three-year-old member of the Bow Valley wolf pack for just over a year after capturing and fitting him with a GPS collar last winter.

It is not uncommon for young wolves to leave their pack in search of new territory of their own, to find mates, or new packs to join.

The most common dispersal age ranges from one-and-a-half to three years.

“This wolf began to show signs of dispersal over the past six months,” said Justin Brisbane, a spokesperson for Banff National Park.

A recent study, Wolves without borders: Transboundary survival of wolves in Banff National Park, concluded wolves that left Banff National Park were 6.7 times more likely to die, particularly during hunting and trapping seasons.

The study, published in Global Conservation and Ecology in December 2020, tracked the survival of 72 radio-collared grey wolves in Banff National Park and the surrounding area over the past 30 years from 1987 to 2018.

One of the authors of that study, Mark Hebblewhite, said it’s not at all surprising that wolf No. 2001 dispersed such a long distance, made it to Montana, or that he died.

“Since wolves first recovered in Banff, there have been dozens – dozens – of wolves that have dispersed such far distances from Banff,” said Hebblewhite, a well-known wolf expert and ecology professor at University of Montana.

“A lot of those movements have been to the south to Montana.”

Hebblewhite said the death of wolves is completely predictable once they leave protected areas like Banff to unprotected landscapes where they face a “stiff mortality penalty.”

“In some of our previous work, we’ve shown that wolves from protected areas may actually be more vulnerable to harvest by humans,” he said.

“They’ve spent so much time being exposed to millions of tourists, photographers, etc., that they are habituated to humans – which puts them at a strong survival disadvantage.”

Wolves in Montana are no longer endangered, but Hebblewhite said the U.S. state has very liberal hunting rules, and perhaps even more liberal trapping regulations than in places like Alberta.

“So any wolf dispersing from protected areas here in Montana, like Glacier and Yellowstone, faces these same gamut of mortality,” he said.

Wolf 2001’s story may be surprising to many, but not unusual. This is not the first well-travelled wolf that biologists have tracked.

In the early 1990s, a female wolf from southern Alberta named Pluie covered an area 10 times the size of Yellowstone National Park and 15 times that of Banff National Park before also being legally shot and killed.

According to the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative, often when wolves and other wildlife leave the safety of a park boundary, they are vulnerable to death, from hunting to being hit by cars, or run-ins with people.

“This is why connecting and protecting the areas near and next to parks is so important,” said Jodi Hilty, Y2Y’s president and chief scientist.

“Wolf 2001’s movements confirms that the Y2Y vision is really important and that we do need connectivity on a large scale.”

Wildlife, including wide-roaming species like wolves, need large, connected landscapes to thrive.

Hilty referred to recent studies that show wildlife movement and connectivity are decreasing with more development and human activity around the world, including in the Bow Valley.

“They’re movements are getting truncated,” she said.

Hilty points to the Three Sisters Mountain Village proposal for a major commercial and residential development east towards Dead Man’s Flats, which has the potential to double Canmore’s population over the next 20 to 30 years.

She said the wildlife corridor through the south side of Canmore is a critical link between Banff National Park and Kananaskis Country – and just one of four east-west connections in the entire 3,200-km Y2Y region.

“The big issue for us is whether we’re willing to sacrifice loss of another corridor, to have one less place the animals will be able to move,” Hilty said.

“If we’re not careful, including in the Y2Y region, we’ll lose that connectivity and we won’t see these kinds of movements like wolf 2001.”

Meanwhile, the future of the Bow Valley pack remains uncertain.

Parks Canada does not know if the alpha female has bred and is expecting pups. Currently, there are two sub-adults and three young-of-last-year wolves in the pack.

The alpha male of the pack was run over and killed on the Trans-Canada Highway west of the Banff townsite last May.

Wolves are resilient and packs tend to bounce back when wolves like No. 2001 die, but the stability and makeup of a pack takes a big hit.

Hunt said Parks has been looking at the size of wolf packs and the stability of packs as part of the bison reintroduction program in the backcountry of Banff National Park.

“When you look at situations where wolves and bison are having a healthy predator-prey relationship, wolf packs are generally larger than what we see here in Banff – and they also have greater pack stability,” he said.

“The premise there is if you’re constantly changing over who the alpha male or the alpha couple is in the pack, they never learn or build those hunting strategies that would be needed for such a large animal as bison.”

This has happened to the Bow Valley pack frequently over time.

With the alpha male killed on the highway last year, Hunt said the hope is one of the sub-adults, or a male wolf from elsewhere, can take on that role within the pack.

“That quick pack turnover doesn’t lead to pups learning from elder wolves of the pack that have had eight or 10 years of experience taking down large prey,” he said.

“Some of the necessary hunting skills require that generational knowledge, as well as larger pack sizes.”