Canmore’s history is built around coal, despite being founded as a railway town, in the fall of 1883.

Canmore’s coal seams are a part of the Cascade Coal Basin, a 155-square-kilometre bed of coal that stretches from Cascade Mountain to the Kananaskis River. In 1904, estimates suggested the basin contained 400 million tons of semi-anthracite coal and 1,200 million tons of low-volatile bituminous coal.

Semi-anthracite coal is rare compared to bituminous coal, and at that time, Pennsylvania was the only place in North America that mined anthracite coal, so finding it in the Bow Valley offered great promise.

Anthracite is a hard and lustrous coal, and while difficult to ignite, it burns hot and with little smoke, making it ideal for generating steam. The more common bituminous coal, meanwhile, is softer, easier to light but smokier than anthracite coal. Bituminous coal was used to make the pillow-shaped briquettes and fuel (coke) for smelting.

The Canadian Anthracite Coal Co. (CACC) – a group of Canadian and American businessmen led by the Stewart brothers, John, McLeod (the mayor of Ottawa) and Archibald – opened the No. 1 Mine along Canmore Creek in 1886. Canmore’s anthracite coal didn’t translate into instant success for the CACC. The high cost of extracting coal in the Rocky Mountains, a result of steep and gassy seams broken by the thrust faults of mountain building, meant Canmore coal came with a higher price, and the CPR – the only viable customer in the region – preferred to pay a lower rate for coal from the Galt mine in Lethbridge.

Unable to win over the CPR, the CACC had no options. The local market was too small to sustain it, and the American market, despite interest from some U.S. states, was closed to Canmore to avoid competition. Given those realities, the CACC directors set out to sell their mines at Canmore and at Anthracite, located near Banff.

The No. 2 Mine looking north towards the tipple, 1956.CMAGS 2008.013.010.001

The No. 2 Mine looking north towards the tipple, 1956.CMAGS 2008.013.010.001

Hobart William McNeill, a lawyer from Oskaloosa, Iowa, offered to buy the company, but as he was facing bankruptcy, the deal fell apart. He instead offered to lease the operation. With the contract signed in 1891, the CACC directors had reason to be optimistic.

The CPR switched to Canmore coal after further tests showed Canmore coal burned more efficiently than Galt coal and Canmore-based railway engineer Charles Carey set a new speed record in a locomotive modified to burn Canmore semi-anthracite coal.

McNeill also had plans to increase production.

The CPR committed to exclusively use Canmore coal on its western leg. CPR general manager William Cornelius Van Horne, meanwhile, stated that “A locomotive driver or fireman who cannot use Canmore coal will get no employment with the CPR.”

By 1892, the CPR was buying three-quarters of the coal mined at Canmore and at Anthracite, but McNeill struggled to meet the CPR’s demand, especially after the Anthracite mine flooded.

McNeill died in 1900, but his son, Walter, persevered and with the backing of the CACC, opened the No. 2 Mine in 1906. Five years later, in 1911, the CACC ended its lease with the H.W. McNeill Co., instead passing it to the Canmore Coal Co., run by two American businessmen Samuel Brinkerhoff Thorne and James B. Neale. Both men were also friends of Frederick E. Weyerhaeuser, one of the CACC directors.

Even though the H.W. McNeill Co. was no longer operating the mines, its influence in Canmore can’t be overstated. McNeill built the framework that would see the CPR come on as Canmore’s main customer, a relationship that would continue until the 1960s. McNeill’s company also oversaw construction of the curling and skating rinks (the first covered rinks in Alberta) and the Canmore Opera House.

The H.W. McNeill Co. also undertook development of the No. 2 Mine with all its accompanying infrastructure, including a wash house that Frank Wheatly, a local miner who would later open a small family-run coal mine west of the old Anthracite mine, would describe as “splendid” and the best in Alberta.

The Canmore Coal Co. (CCC) took over operation of the No. 1 Mine, closing it as planned in 1916 and the No. 2 Mine, along with the Rundle Mountain Trading Co.

While businessmen (Thorne and Neale profited handsomely from operating the Canmore mines), they also believed the community should benefit from the mines. During the CCC’s tenure in Canmore, which ended in 1938, the company – also with the backing and support of the CACC – built a briquette plant, Memorial Hall for veterans of the First World War, the Directors’ Cabin along the Bow River, the Model School and company housing in South Canmore. The CCC opened a hospital, as well. The CCC also saw that electricity was installed in buildings in Mineside.

Canmore miner Joe Miskow standing in front of a mine cart, 1962CMAGS 2008.017.004.001

Canmore miner Joe Miskow standing in front of a mine cart, 1962CMAGS 2008.017.004.001

Following the war, business continued to be good as increasing demand for Canmore coal led the mines, in 1929, to reach a peacetime record of 271,000 tons with most of it going to the CPR.

The good times, of course, ended with the Great Depression. Sales to the CPR dropped from the 1929 record of 271,000 tons to a low of 100,000 tons a year. Miners saw their working days cut to about 10 days a month, as opposed to their usual six days a week.

The CACC renewed the CCC’s contract in 1936 for 25 years, but by 1938, Archibald Stewart had grown increasingly frustrated with the arrangement. He believed the CACC should be operating the mines and reaping the benefits. Stewart pushed through a proposal to buy out the CCC and form a subsidiary of the CACC – Canmore Mines Ltd. – to run Canmore’s mines.

Instead of moving to cut costs during the tail end of the depression, Canmore Mines Ltd. (CML) initiated a program of improvements and enhancements that included opening the No. 4 Mine.

With the start of the Second World War in 1939, Canmore was able to take immediate advantage of the increased need for coal, and by 1944, yearly coal sales had reached over 340,000 tons, while the sale of briquettes had hit 100,000 tons.

The war also brought benefits to Canmore miners at least, after coal miners across Western Canada – frustrated at the long hours the government required them to work – began striking. The agreements that followed gave miners a raise and two-weeks paid vacation. In Canmore, miners saw a second raise following another strike in 1946. Canmore Mines Ltd. also agreed to reduce the workweek to five days a week and put three cents per ton into a relief fund for miners.

Like the end of the First World War, when everything seemed rosy, there was another downturn on its way following the end of the Second World War. This time it was brought on by the discovery of oil and gas in the late 1940s at Leduc, Redwater and Pembina. The CPR began to switch to diesel locomotives, and by 1955, Canmore miners were working two to three days a week. The CPR stopped buying Canmore coal altogether in 1960 after it had completely switched to diesel locomotives.

But Canmore Mines Ltd. had not been idle. As the CPR’s orders decreased, Canmore Mines moved to take advantage of a new market: the Japanese steel and chemical industries. By 1957, Japan had ordered 400,000 tons of coal a year.

Canmore also began to produce coke, selling it to American iron ore smelters after Canmore-born mine engineer and general manager Walter Riva designed a high-temperature coking plant in 1962.

In 1967, Canmore negotiated a $50 million deal with its Japanese customers for 500,000 tons of coal a year; however, there was a problem: Canmore was only producing 300,000 tons a year. Canmore Mines Ltd. turned to strip mines to bump production. Strip mines at Quarry Lake and the Nordic Centre allowed Canmore Mines Ltd. to add 350,000 tons to the order over seven years, but it wasn’t enough.

The only way Canmore Mines could fulfill its contract was to open a new mine, but the directors weren’t interested in footing the bill, so they instead decided to sell.

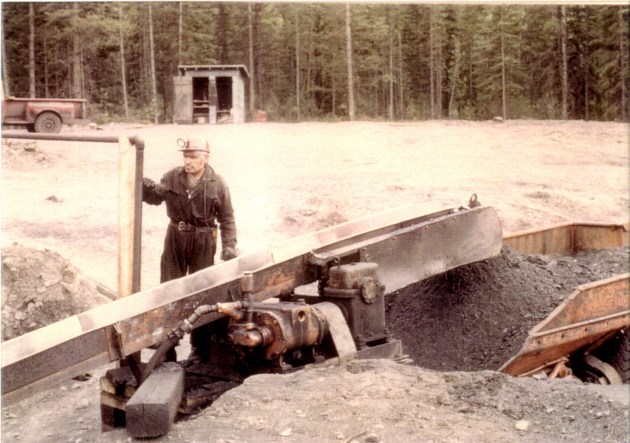

An unidentified Canmore coal miner loads a dump truck with coal, ca. 1970s.CMAGS 2008.030.004.001

An unidentified Canmore coal miner loads a dump truck with coal, ca. 1970s.CMAGS 2008.030.004.001

While coal offered a good alternative as a fuel, a sharp increase in shipping costs made it practically impossible to move coal and to open new markets. At the same time, Canmore faced competition from Australia, new Canadian environmental regulations and demands from the Japanese for a lower price.

Dillingham lost $3 million between 1977 and 1979 alone.

Dillingham considered selling the mines at first, but by the summer of 1979, the company instead decided to close the mines altogether. On July 9, mine foremen were called to a meeting at the Union Hall where they were told the mines would close on Friday, July 13: a day that became known as “Black Friday.”

After 93 years, Canmore was no longer a coal-mining town.