CANMORE – Hazy smoke-filled skies have become a common sight during the summers in the Canadian Rocky Mountains.

While people live and visit this area to be surrounded by some of the most beautiful natural spots in North America, the same trees can be a double-edged sword and possible risk for the Bow Valley.

During the lengthy public hearings for the proposed Three Sisters Mountain Village area structure plans, some delegates requested a regional strategy for wildfire risk be completed before decisions are made.

“The Towns of Banff and Canmore have to deal with that they are right next to huge wilderness and park areas that have these fires. … It’s not just all green trees, blue skies and grizzly bears. It has a bit of a downside in that it burns,” said Cliff White, who worked with Parks Canada and was the former national fire management coordinator for the agency.

Though FireSmart plans are thorough in Canmore, the bigger risk is beyond the town’s limits, White said. The addition of trees in the area, ignition probability and the trend of drying weather is leading to an increase in the likelihood of fires.

He said a regional plan before any development proceeds, which examines 15 to 20 kilometres beyond Canmore, would help further mitigate risk.

“What tends to happen is people overbuild, everybody gets too worried to do any prescribed burning and then they just try to hang on to it for year in year out until a wildfire occurs. You then have massive smoke, massive evacuations, it's just the worst of all worlds because it wasn't really thought through above what would be sort of a nice balanced approach to how to coexist with nature.”

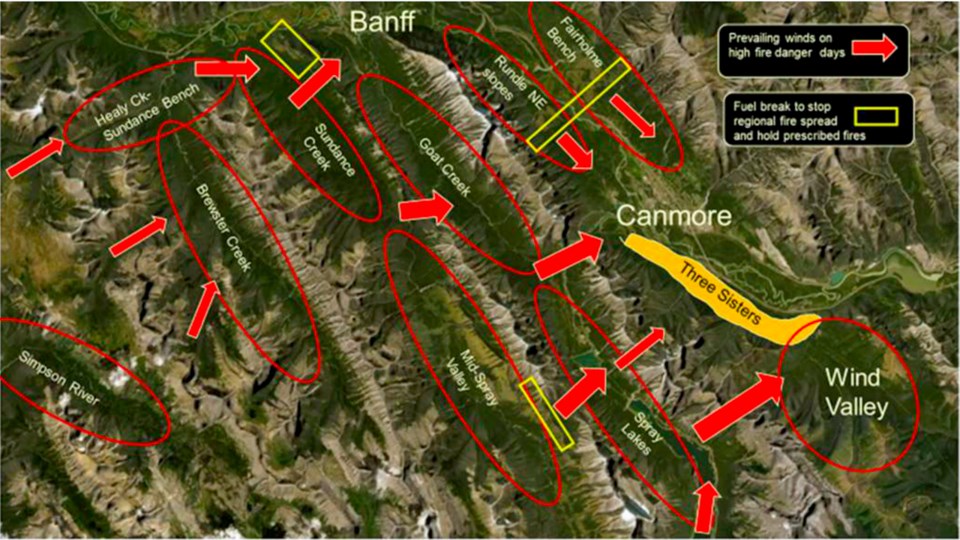

A diagram of wind direction and existing fuel breaks to stop potential regional fire spread.Courtesy of Cliff White

A diagram of wind direction and existing fuel breaks to stop potential regional fire spread.Courtesy of Cliff WhiteWhite, who managed Banff’s ecosystem research and restoration section for about two decades, said Banff National Park and the Alberta government have a history of detailed regional work.

A regional strategy typically has all three levels of government come to the table to discuss vegetation, wind patterns and slope angle or the “triangle of fuel, weather and terrain.”

He gave the example of the R11 Forest Management Plan for provincial lands in the MD of Bighorn along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains that comprise 521,900 hectares (1.29 million acres) of land, with the North Saskatchewan River cutting through the middle of the region.

An aspect of the plan was integrating national park, wildlife and forestry interests in the region to help manage the long-term fire risk. White said it took about eight months to complete, but set out prescribed burn planning and fire management.

Canmore residents Shaun Peter and Tim Murphy also raised the fire risk and evacuation alarm at the public hearings. If TSMV’s bonus toolkit were fully realized, it could eventually lead to an extra 14,000 people in Canmore in 20 to 30 years, which could mean about 20,000 people living on the south side of the river.

If the worst were to happen – such as the 2016 wildfire in Fort McMurray and 2018 in Paradise, California – the extra population could prove overwhelming for the Eighth Avenue Bridge and Three Sisters Parkway, Peter said, arguing for a regional wildfire strategy.

“It’s like we’ve built a theatre and we’re trying to figure out how many people we can safely allow in the theatre," he said. "We can’t increase the fire exits, they’ve already been built. ... When it comes to fire evacuation, we’re all just running for the doors. We need to know how many people the theatre can hold before it’s approved to be built.”

A spokesperson for the Town of Canmore said its evacuation plan is reviewed regularly and updated as growth and development takes place.

Legislatively, the province doesn’t require a municipality or developer to do a regional fire risk assessment plan prior to development. However, regions in the Bow Valley are vigilant in mitigation efforts and have long-term vegetation management strategies in place. FireSmart recommendations also place a priority on residents to play a role in prevention on their property.

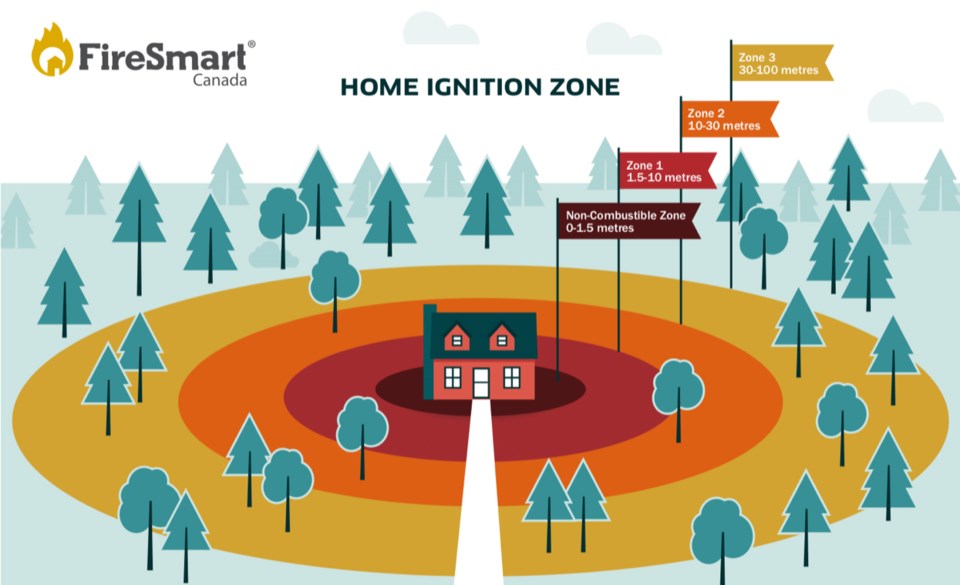

FireSmart

Home Ignition Zone

Non-combustible zone: From the structure outwards for 1.5 metres to clear tree branches and only have non-combustible material

Zone 1: From 1.5m to 10m, vegetation management is meant to clear anything that may cause a fire

Zone 2: 10m to 30m from the building, is meant to have an environment that may only spread fire of a lower intensity and rate of spread

Zone 3: From 30m to 100m, clearing is only needed if it has high-extreme levels from heavy continuous coniferous forest vegetation

Guidelines from FireSmart Canada show the four home ignition zones.Courtesy of FireSmart Canada

Guidelines from FireSmart Canada show the four home ignition zones.Courtesy of FireSmart Canada

Jen Beverly, an assistant professor of woodland fire with the University of Alberta’s renewable resources department, said strategic risk assessments done by communities have evolved in recent decades to include evacuation and contingency planning for specific kinds of fire scenarios.

She noted trigger points in and around a community can be established, so if a fire hits a predefined area, it can lead to an evacuation, if necessary.

“When we're looking at risk to communities in Canada, and certainly in Alberta, these are really low probability, high consequences. The chance a particular location in Alberta is going to burn this summer is really low. … The probabilities of a specific location burning over the next year, it's really low. From a risk terminology, there are low probability, high consequence.”

Beverly's research has analyzed the routes fire may travel – also called fire pathways – and the connectivity of fuels in relation to a built-up environment. It involves working with transportation engineers to assist with planning for evacuation routes.

“In these low probability, high consequence situations, you need to do more contingency and scenario planning, and that can be complementary to other types of strategic assessments that get done like threat assessments, looking at the fuels among other things,” said Beverly, who runs Wildfire Analytics and is a former research scientist with the Canadian Forest Service.

“I think it becomes really important in places like Canmore where you've got a lot of fuel, you've got a lot of potential for fire, but because of ignitions, weather and other factors you haven't necessarily had a lot of historical fire in those areas. The probabilities are low, but if it does happen and the conditions do align, the consequences are going to be really really high.”

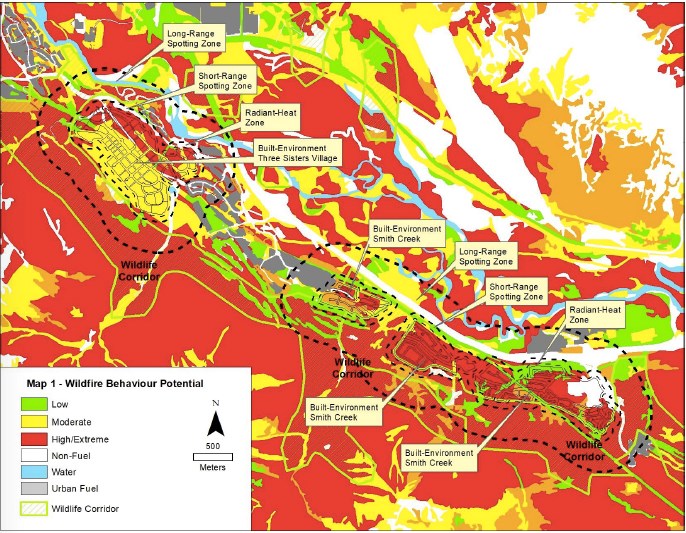

The wildfire behaviour potential in the Town of Canmore.Submitted photo

The wildfire behaviour potential in the Town of Canmore.Submitted photoWith or without any future development, the risk of wildfire will always remain in the Bow Valley. The main goal is to mitigate as much risk as possible.

FireSmart planning attempts just that, since the only way to completely erase the danger is eliminating the forests people love. The measures are ultimately designed to buy time for firefighters to contain a fire or at the worst, provide extra time to evacuate.

“The threat of wildfire in Bow Valley and the Town of Canmore definitely exists,” said Stew Walkinshaw of the Canmore-based Montane Forest Management, who conducted the wildfire risk assessment for TSMV, at the public hearing.

“There’s no question we can have large wildfires in the valley and the Town of Canmore, but developments can be mitigated by using wise FireSmart practices starting at the home and working out from there.”

The development level assessment ranged wildfire behaviour from low to high-extreme within 100 metres on the proposed TSMV lands due to a dense mature coniferous forest on slopes and a mixture of cured-grass in areas.

A landscape assessment showed the wildfire behaviour within 500 metres of the proposed development is high-extreme because of the possibility of high winds, large amount of pine and spruce trees and the risk of embers spreading.

However, if the structural, infrastructure and vegetation management mitigation is followed it would “result in a community that is much less prone to wildfire losses and improve firefighter response effectiveness and safety,” according to the study.

The assessment stated fire-rated or fire-resistant exterior structural materials “will reduce” the possibility of fire. It also recommends all buildings follow Canmore’s engineering design and construction guidelines.

Canmore’s land use bylaw adopted the use of fire-rated roofing materials in 1999. It requires wildfire risk assessment for all subdivision applications and all habitable buildings are required to have a minimum of 1.5 metres of non-combustible landscape around the building.

Canmore has received national recognition for its fire mitigation efforts in the past. Canmore Fire-Rescue also regularly trains for wildfire exercises with wildland-urban protection equipment such as portable sprinklers that can be used at the edge of a development.

The department also offers free FireSmart home and property visits to conduct assessments and risk evaluations to give residents personalized recommendations.

The Town’s 2018 Wildfire Mitigation Strategy Review – also completed by Walkinshaw – highlighted the main source of fuel to spread a fire were the numerous pine and spruce trees in the region, which could lead to embers spreading into Canmore. If that were to happen, the review theorizes it would likely spread west to east.

The review noted the fuel breaks at Carrot Creek and Canmore Nordic Centre West “provide an excellent containment line for wildfire operations.”

Fuel breaks or thinning of trees is a constant occurrence in the Bow Valley.

Between 2010 and 2017, Canmore, private companies and the province reduced about 138 hectares of trees in the town, the 2018 review states.

According to the 2020 State of Canada’s Forests by Natural Resources Canada, the country has 347 million hectares of forest – about nine per cent of the world’s forest – and another estimated 50 million hectares in urban areas. The majority of those – 90 per cent – are found on public lands.

The Wildfire Management Program and the 2015 Fire Season prepared for Alberta’s Agricultural and Forestry ministry found in 1999 Canmore had 626.9 hectares in a perimeter of 46.6 km. By 2015, it had expanded to 792 hectares in a 60.7 km perimeter. While minimal, the report wrote it “elevates the risk from wildfire to lives and property in the woodland urban interface.”

The 2019 Spring Wildfire Review had the province averaging 1,266 wildfires a year between 1990 and 2019 – most being in northern Alberta. Of those, 44 per cent were naturally occurring with the remainder human-caused and nearly 95 per cent were extinguished within 24 hours. According to statistics from Natural Resources Canada, there are about 8,000 wildfires each year, burning an annual two to two-and-a-half million hectares.

Alberta’s Wildfire Management Branch put significant resources into prevention and containment efforts, covering about 39 million hectares and spent $438.6 million in 2019.

The evolving role of climate change could also impact wildfires. Though not fully known, researchers from the Canadian Forest Services wrote a 2017 paper that forecast a 50 per cent increase in western Canada.

“Our results suggest that climate change over the next century may have significant impacts on fire spread days in almost all parts of Canada’s forested landmass; the number of fire spread days could experience a two-to-three fold increase under a high CO2 forcing scenario in eastern Canada, and a more than 50 per cent increase in western Canada, where the fire potential is already high,” the paper stated.

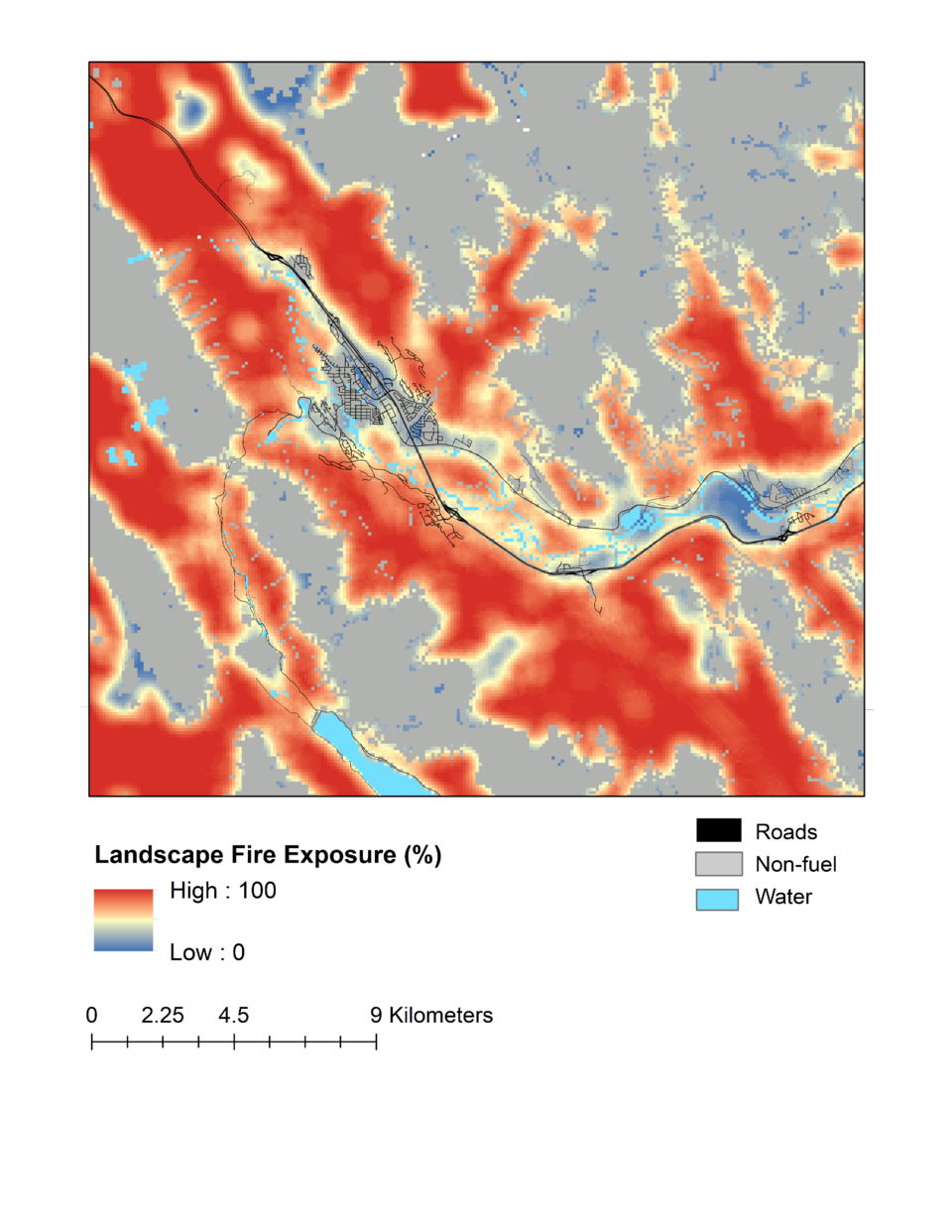

In a paper released earlier this year – a simple metric of landscape fire exposure – Beverly and two colleagues developed an exposure metric to assist with risk assessment. In working with Alberta Wildfire, they developed an exposure assessment for the province that focuses on landscape fire exposure.

An exposure assessment developed by Wildfire Analytics and Alberta Wildfire focused on the risk of landscape fire in Alberta. A snapshot shows Canmore on the provincial assessment.Courtesy of Jen Beverly

An exposure assessment developed by Wildfire Analytics and Alberta Wildfire focused on the risk of landscape fire in Alberta. A snapshot shows Canmore on the provincial assessment.Courtesy of Jen BeverlyShe said different risks can always be mapped out such as the amount of fuel, potential fire behaviour and exposure, but they are focusing more on fire pathways, where to position containment lines and regional fuel breaks to be more proactive in preventing risk.

Beverly noted a challenge is it involves many people, groups and levels of government with different perspectives and possibly competing objectives.

“It doesn’t answer all the questions," she said. "It’s not a miracle solution. It’s one piece of information and a new approach. We’re now extending that work to look at the fire pathways around communities and trying to better understand the flow of fire through the landscape, so if you can understand where fire’s going to flow, then you can look for places to cut it off.”

White said significant fuel breaks have been done regionally – such as the Harvie Heights area and Goat Gap in the mid-Spray Valley – but the comprehensive regional analysis is needed.

He said from Goat Creek over Whiteman’s Pass, Spray Lakes over the Three Sisters Creek Gap and the Spray Lakes over Wind Pass into the Wind Valley and Wind Ridge remain at risk, which he called “one of the riskier and more difficult to mitigate situations in the Canadian Rockies.”

White noted the wind rapidly accelerates into the Bow Valley and the majority of the area is covered with mature lodgepole pine and spruce trees. A worst-case scenario could see fire spotting – where embers reach the town – over Wind Pass or Wind Valley, descending quickly to send an “ember shower” across the valley.

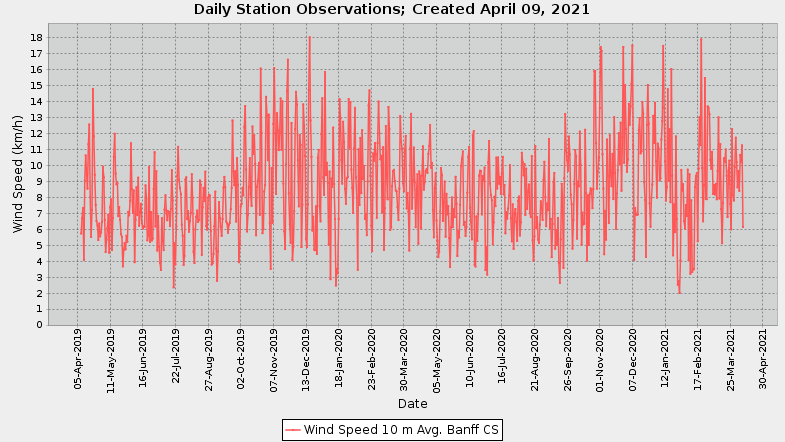

Walkinshaw’s report listed an approximate 35 days each year where there are very high or extreme fire danger levels and winds, mainly from the southwest and west of the town. Fire weather data over a 20-year period is used from the Banff weather station to determine the information.

Weather data from April 2019 to April 2021 at the Banff National Park weather station shows an average speed between 3 km/h to about 13.5 km/h from March to September.Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Weather data from April 2019 to April 2021 at the Banff National Park weather station shows an average speed between 3 km/h to about 13.5 km/h from March to September.Alberta Agriculture and ForestryHistorical weather data from the Alberta Agriculture and Forestry site for the past two years from the Banff weather station has the wind primarily moving west to east in the region. It also shows at a height of 10 metres, the wind speed averages between roughly three km/h to 13.5 km/h from March to the end of September. For the same two-year time period, the weather station in Bow Valley Provincial Park lists between two km/h to about 19km/h.

However, wind gusts – when the wind significantly but briefly picks up – have reached recorded speeds of 76 km/h.

The area south of the proposed developed “remains unassisted and largely unmitigated,” White argues, adding Wind Valley was set aside as a mitigation for the eventual development. But with the development possibly being more intense it may have to be fuel treated as “an unintended consequence of overdevelopment.”

He said the original development of the golf course would have worked both for the wildlife corridors and wildfire mitigation.

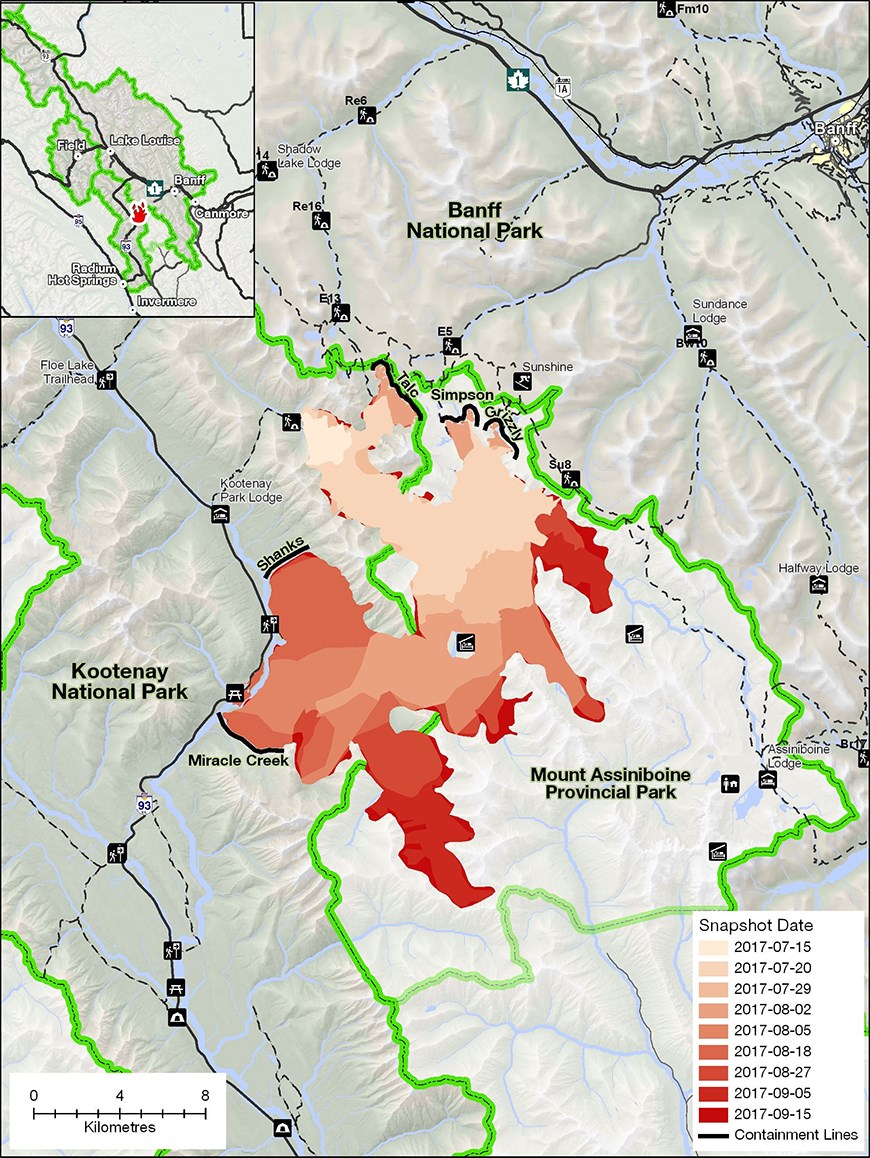

A new fuel break – likely to stretch about six kilometres – along Sulphur Mountain is being made following the Verdant Creek wildfire in 2017 that began from lightning and dry conditions.

Snapshots of the 2017 Verdant Creek wildfire and it's spread over a two month period.Photo courtesy of Parks Canada

Snapshots of the 2017 Verdant Creek wildfire and it's spread over a two month period.Photo courtesy of Parks CanadaIt grew to envelop 18,017 hectares, according the Parks Canada, to the southwest of Banff. The fuel break work began in 2018 west of Sulphur Mountain after planning was done in 2016 and will see about 350 hectares of trees removed.

“People had been slightly worried about Sulphur Mountain in Banff over the years, but hadn’t given too much thought, and a bit of fuel break work was done," White said. "But the 2017 fire was about a day away from hitting the side of Sulphur (Mountain). … You’ve got to look at what your risks are, particularly with the ember showers where you end up with rapidly spreading fire that's lofting a bunch of sparks into the air.”