A new study looking at one of the enigmatic creatures of the 505-million-year-old Burgess Shale fossil beds has shown that one of our oldest relatives – albeit a distant one – is, in fact, a worm.

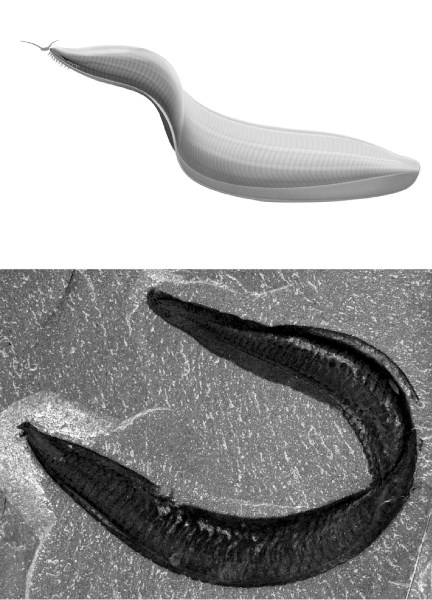

Scientists with the Royal Ontario Museum, University of Cambridge and University of Toronto have discovered that Pikaia gracilens, an extinct worm the length of a person’s thumb whose fossil remains are found only at the Burgess Shale beds in Yoho National Park, had a primitive notochord, a flexible rod-shaped structure found in the embryo of all chordates that in most vertebrates – including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals – becomes part of the spinal column.

“Pikaia represents a very, very distant relative to us. We cannot say it is directly related to us, but we can say it is a very, very distant relative,” said Jean-Bernard Caron, curator of Invertebrate Paleontology at the ROM and co-author of the study published March 5 in the British scientific journal Biological Review.

“This is an animal that allows us to understand our roots and our origin in the sense that they share features with us at a very deep level,” Caron said Monday (March 12).

As part of their work, Simon Conway Morris of the University of Cambridge and Caron found Pikaia’s eel-like body had myomeres or “blocks of skeletal muscle tissue characteristic of chordates, as well as evidence of a vascular system, including blood vessels,” Conway Morris stated in a release from Parks Canada.

As a result, he described myomeres as the ‘smoking gun’ that identifies Pikaia as a chordate.

“The discovery of myomeres provides the smoking gun that we have long been seeking,” said Conway Morris. “With myomeres, a nerve chord, a notochord and a vascular system all identified, this study clearly places Pikaia as one of the planet’s first and most primitive chordate animals. So next time we put the family photograph on the mantle-piece, there in the background will be Pikaia.”

Pikaia appears to have been a filter feeder that lived on the sea floor. It has two tentacles on its head that Caron said could be sensory organs. Pikaia also sports nine pairs of branching appendages near its small head, for which Caron said the purpose is still unknown.

“Those are enigmatic. We don’t really know their function. They might be used to help the animal direct food particles towards the front or they could have been used for respiration,” he said.

The end of each appendage is tipped in small pores that may have acted like gills, drawing oxygen from water as it was pushed from the animal’s pharynx or throat and out the pores. A long fin runs along both the top and bottom of Pikaia’s body.

The story of Pikaia is important, Caron said, as not only does it represent part of the origin story for vertebrates, it is also an elusive story that puzzled paleontologists for decades.

Charles Doolittle Walcott, the American paleontologist who discovered the Burgess Shale fossil bed in 1911 – which would become the Walcott Quarry – believed Pikaia was an annelid or ringed worm, a phylum of worms that includes leeches and earthworms, which are not chordates. Subsequent generations of scientists, however, speculated Pikaia – one of the rarer Burgess Shale fossils – had a primitive notochord.

But it was not until Conway Morris and Caron took a hard look at 114 fossilized specimens of Pikaia held at the ROM and the Natural History Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. that they began to understand Pikaia’s identity.

“Pikaia has been left in the dark for too long, since the first specimens were discovered,” Caron said. “It was really a thorn in the leg of most of my colleagues and past paleontologists who had worked on the Burgess Shale in the sense that nothing had been made public and accessible to other researchers. It is a big relief for all of us. It is long overdue research and I think in many ways it should probably allow a lot of my colleagues to engage in the topic of early chordate evolution.”

It was also one of the few Burgess Shale creatures discovered and described by Walcott that had not yet been re-described by modern scientists who have a greater level of knowledge about the Burgess Shale creatures and are aided by modern technology, such as electron microscopes and high-resolution digital cameras, as well.

Both aspects allowed Caron and Conway Morris to end the speculation and confirm Pikaia shares the distinction of being one of the earliest chordates on the planet with the fish-like animal Haikouella lanceolata, an approximately 525-million-year creature found in fossil beds in China.

Along with the fact that Pikaia is a chordate and our distant cousin, the fossilized specimens of Pikaia demonstrate the animals likely struggled to free themselves after they had been buried by underwater mudslides.

“What is interesting about these orientations is that you see a lot of animals that seem to be twisted in all directions. The bodies are very twisted and bent very sharply in different directions. We think this is a reaction to burial,” Caron said.

“It could be one of the rare fossils from the Burgess Shale that shows this sort of thing. When the animals were buried, they were probably buried alive and they might actually have reacted to this burial, maybe trying to escape, and what you see here is basically the attempt to escape perhaps at least for the specimens buried at this high angle or twist.”

For Parks Canada, which is responsible for protecting and preserving the Burgess Shale sites and sharing the discoveries, finding a creature of Pikaia’s stature is like winning the top prize in hockey, said Parks representative Omar McDadi.

“This finding is kind of like the Stanley Cup of fossil discoveries,” McDadi said. “It is really huge and has big implications and we think it is really neat that it was found right here in our own backyard in the heart of the Canadian Rockies in Yoho National Park.

“Parks Canada works really hard to make the site accessible to scientists for cutting edge research like this, but also for the public. There are many ways to discover the Burgess Shale, be it in person or from the comfort of your own home.

“It has never been so easy to learn about the Burgess Shale fossil beds,” McDadi said. “The conditions required for the immaculate preservation you find at the Burgess Shale is such that you find almost nowhere else on Earth.

“We are very lucky this was found in the national parks. This discovery does emphasize the importance of preserving this site and keeping it open.”