It's hard to imagine what the Bow Valley and the eastern slopes of the Canadian Rockies would look like today if not for the environmental stewardship of groups such as the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Southern Alberta chapter (CPAWS).

It's hard to imagine what the Bow Valley and the eastern slopes of the Canadian Rockies would look like today if not for the environmental stewardship of groups such as the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Southern Alberta chapter (CPAWS).

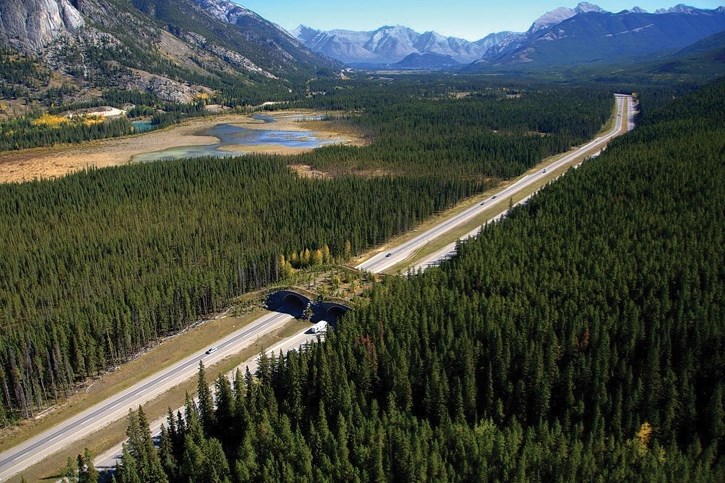

For one, world-renowned wildlife crossings that span the Trans-Canada Highway might not exist and Banff would be a sprawling urban centre many times larger than it is today.

Instead, thanks to 50 years of environmental leadership, the CPAWS Southern Alberta chapter can be credited for helping protect many of the region's most treasured areas, from the Whaleback of southwestern Alberta to Spray Valley Provincial Park.

"The Bow Valley would look vastly different if it wasn't for the work of our organization and others," said Anne-Marie Syslak, executive director for the southern Alberta chapter.

"Although we know it the way it is today, the amount of development that we helped to keep at bay is quite overwhelming."

Her comments couldn't be more accurate as the list of accomplishments the local organization has achieved over the last five decades is staggering.

From helping to defeat an Olympic bid and large-scale development in Banff in 1972 to more recently spearheading the creation of Castle Provincial Park in 2017, the southern chapter has been an influential voice since its inception and continues to be a leading conservation organization across the country.

The beginning of an environmental movement

Like many prominent environmental organizations that exist today, the southern Alberta chapter can trace its roots back to the late 1960s, a period when environmental concerns began to bubble to the surface of public discourse.

Leading the charge locally was Gordon Nelson, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Calgary, and Harvey Buckmaster, an associate professor of physics.

"What happened with CPAWS was, in a way, a part of the rising environmental concern at the time," said Nelson, pointing to the growing number of academics concerned about the impact humans were having on the environment.

"It was a turning point in my life because at the time I was doing geomorphology, glaciology and things like that, but I had this secondary interest in human ecology and human impact on the environment, which wasn't a very old field of study."

Inspired by this new field of research and concerned about a number of developments proposed in Banff National Park, the two men began holding informal meetings with like-minded individuals, many of whom were their graduate students.

By 1965 the grassroots organization formed an unofficial relationship with the National and Provincial Parks Association of Canada (NPPAC) in Toronto, beginning what would eventually become the Calgary/Banff chapter two years later.

For the next decade the group focused its conservation efforts on three major issues; a proposed master plan to expand roads and facilities in Banff National Park, the expansion of the Lake Louise Ski Resort and an Olympic bid in Banff.

Eventually, through public talks, written submissions and other activities, these proposals were all withdrawn or rejected - a significant feat for the grassroots organization and the first of a string of conservation victories that would continue over the next 50 years.

An era of protest

Inspired by the impending Lake Louise development and the first national park management plan, Rosemary Nation, a past board chair, decided to volunteer with the local chapter in the late 1970s, a period which she described as "controversial.

"I decided to join the organization largely because of all of the controversy about developing Village Lake Louise in the '70s," said Nation, who was a university student at the time.

During this period she said the idea of public consultations for projects was still in its infancy.

"Parks Canada just started doing some public consultations in the '70s and the idea of an environmental assessment of a project, for example Village Lake Louise, really wasn't even thought of when they made their proposal."

Spurred by the lack of public input, the group helped organize protests in Banff and Vancouver.

"The idea was to try and bring attention to the fact that there was land worth preserving and that resource and other development might not be considering its value as preserved wilderness as opposed to a money maker for a business," said Nation.

Through protests, responding to development proposals and meeting government officials, the local chapter's message eventually started to get through.

"I think the Parks Canada administration did start to realize they had to involve people from the environmental side in their consideration when someone brought forth a proposal," said Nation.

The 1980s also marked a period of financial uncertainty for the local chapter until a government-run casino netted the non-profit group $29,000, a significant sum that allowed the group to refocus its energy on its conservation work.

Nation also managed to regularly meet with government officials during this period and in 1985 the NPPAC was renamed the Canadian Parks And Wilderness Society (CPAWS), cementing it as a leading environment organization across the country.

"As the president of the Banff/Calgary chapter I met with quite a number of ministers of the environment as they would change so we could introduce our organization and talk to them about what we stood for and what we were willing to do."

Perhaps one of the most enduring legacies of the newly minted organization came just three years later in 1988 when it helped influence an amendment to the National Parks Act, which included language to prioritize the ecological integrity of Canada's national parks.

Today, environmentalists both within the organization and outside of it rely on this legal framework to resist and, in some cases stop, development from taking place in Canada's national parks.

A time of significant change and accomplishments

Throughout the 1990s the local chapter continued to build on its previous conservation work, including launching the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative in 1993, a joint Canada-U.S. nonprofit organization that connects and protects habitat from Yellowstone to Yukon.

Two years later in 1995, CPAWS Southern Alberta chapter was instrumental in developing wildlife crossings in Banff National Park, helping enhance and preserve important wildlife corridors throughout the park.

"We needed to make the case for wide span overpasses," said Wendy Francis, a past board chair and conservation director who was directly involved with the campaign.

At the time, the federal government planned to twin the highway from the east gate to the Sunshine turnoff, but had no plans to build any wildlife overpasses.

"To this day there are no overpasses there. Instead, the government built mostly culvert underpasses and a couple of wide span underpasses," said Francis.

"The research showed the underpasses were not working and that certain animals, especially large carnivores and weary animals, were not using the underpasses."

In an effort to change that, CPAWS and the Bow Valley Naturalists launched a campaign to get the federal government to build wildlife overpasses during the second phase of the highway expansion from the Sunshine turnoff to Castle Mountain junction.

By 1995 its efforts paid off and Parks Canada built the first two overpasses between Sunshine and Lake Louise.

Building on its success, the following year the group helped usher through the Banff Bow Valley Study on Ecological Integrity, which led to legal caps on commercial development in Banff - a significant victory that continues to limit the amount of development in the town site today.

While both of these achievements were instrumental in its conservation efforts, one of the most significant changes took place behind the scenes with the creation of the chapter's first paid position.

"There were very few paid people doing conservation work in the late '80s and early '90s. The vast majority of conservation advocacy was being undertaken by volunteers, most of whom had full time jobs, so we were doing it at our kitchen tables in the evenings and on the weekends," said Francis, who became the southern chapter's first paid conservation officer in 1996 after managing to raise funds to pay for the position.

"The capacity to do conservation work grew in many senses because there were groups not only like CPAWS in southern and northern Alberta, but the Alberta Wilderness Association and World Wildlife Fund and other others who had paid staff doing conservation work in the province."

With a paid conservation officer at the helm of the organization, the southern chapter continued to build on its early achievements helping to establish the Elbow-Sheep Wildland and Bow Valley Wildland Provincial Parks, as well as creation of a Kananaskis Country Recreational Development Policy, which defined the region and its land use policies.

One of its biggest accomplishments during this time was the successful intervention to prevent exploratory well drilling in the Whaleback, a proud moment for many CPAWS members, including Francis.

"We had never heard about the Whaleback, it was an area the Alberta Wilderness Association identified as having really high bioversity values," recalled Francis.

"In 1992, Amoco bought a bunch of leases in the Whaleback area and announced it intended to build a very large sour gas field with dozens of wells."

Spurred to action to protect the area, Francis and other volunteers with the southern Alberta chapter decided to launch an awareness campaign.

"We had two goals. One was to stop the Amoco development and the second was to get the Whaleback protected in perpetuity."

In June of 1992, the Energy Resources Conservation Board, now known as the Alberta Energy Regulator, sided with CPAWS and other environment organizations during a public hearing to stop the development.

"It was one of the first and only times that energy development in Alberta has been turned down because of environmental concerns," said Francis.

For the next six years the organization continued to campaign for the protection of the area and in 1999 the Nature Conservancy of Canada was able to raise enough money to buy the leases back from Amoco, allowing the provincial government to establish Bob Creek Wildland Provincial Park and the Black Creek Heritage Rangeland - essentially protecting the Whaleback region from development.

Education becomes strategic conservation tool

While most of the chapter's achievements resulted in the protection of sensitive land, one of its biggest in-house accomplishments was the launch of its education program in 1997.

Founded by Gareth Thomson, the program was the first of its kind for CPAWS chapters across the country and other conservation organizations in Alberta.

The idea behind the program was to increase engagement and conservation through multiple classroom and on-site visits to educate students about issues that were important, but not always urgent.

"We encouraged students to take well informed action as a result of what they learned," said Thomson, who was the chapter's education director for seven years.

"We didn't prescribe what kind of action, but we did ask them to consider some kind of action. We believe it's important to help students with how to think, not what to think."

One of the most successful student-led initiatives was a postcard campaign that ultimately secured federal funding to build several wildlife crossing structures in the Bow Valley, including an underpass near Dead Man's Flats.

The education program has continued to expand over the last 20 years and in 2016 won an award from the Canadian Network for Environmental Education and Communication (EECOM).

New millennium marks more milestones

After securing some big wins in the 1990s, the southern chapter continued to build on its momentum in stopping the development of a major resort in Spray Valley in 2000 and the establishment of Spray Valley Provincial Park.

"If that area had been developed as was proposed, it would have been completely unrecognizable today," said Phil Nykyforuk, current chair of the board.

He estimates that with the establishment of Spray Valley Provincial Park, which was subsequently expanded in 2004 alongside Bow Valley Wildland Provincial Park, well over 50 per cent of Kananaskis Country is now protected land, representing up to 2,500 square kilometres.

Adding to the amount of land protected from development, in early 2017 the province made good on years of discussions to establish Castle Provincial Park and expand Castle Wildland Provincial Park immediately north of Waterton Lakes of National Park.

"That was a real watershed moment," said Nykyforuk, explaining it took several decades to establish the park.

Conservation remains a challenge

Despite the chapter's achievements over the past five decades, Syslak admitted the chapter has faced its fair share of challenges and in some cases failed to stop development from proceeding.

"Sometimes conservation in Alberta, in particular, is a challenging endeavour," said Syslak, pointing to the Glacier Skywalk along the Icefields Parkway as an example where development trumped conservation.

"That was an area that was a public viewpoint that became privatized and we fought to not have that developed and we didn't win that one."

Other examples include the recent approval to expand Lake Louise Ski Resort.

"It's not a done deal, but certainly with the site guidelines they have, a blue print that could allow for doubling capacity of the ski hill, that's certainly concerning in the context of the national park," said Syslak.

"These areas are supposed to be our most protected areas and that doesn't mean that we can't go and enjoy them and use them responsibly, but certainly in our view we want to maintain the current footprint and not expand it."

With new battles brewing on the horizon there's no denying CPAWS will have its hands full in the years ahead, but if its past is any indication of its future, the organization is more than prepared to continue the fight to protect and preserve the region's natural environment.

"We've accomplished a lot over 50 years and have certainly left a legacy in our region that Albertans will continue to enjoy into the future."

CPAWS' Southern Alberta History

1967 The first regional chapter of the National and Provincial Parks Association of Canada (NPPAC) was established in Calgary.

1971 Helped defeat the Prairie River Improvement Plan, which would have diverted water from northern Alberta watersheds to the southern part of the province.

1972 Helped defeat a large-scale development and Olympic bid in Banff National Park.

1975 Fish Creek Park was established, with the support of the NPPAC.

1980 Nose Hill Park, initially proposed by Harvey Buckmaster (NPPAC), was designated as a protected area.

1985 The NPPAC was renamed the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS).

1988 Influenced an amendment to the National Parks Act which included wording to prioritize ecological integrity first in park management.

1992-3 Helped protect Wind Valley from development.

1993 Helped found the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative.

1994 Hired the first staff position.

1995 Instrumental in leading and shaping now world-famous wildlife crossing structures in Banff National Park.

1996 The Banff Bow Valley Study on Ecological Integrity resulted in caps on commercial development in Banff National Park.

1997 Environmental education program began. CPAWS SAB is the only chapter with this unique program.

1998 Elbow-Sheep Wildland and Bow Valley Wildland Provincial Parks were established.

1999 Defeated the proposed and flawed Alberta Natural Heritage Act.

1999 Pressed for K-Country Recreational Development Policy, which defined the region and its land use policy.

1999 Intervened to prevent exploratory well drilling in the Whaleback. Bob Creek Wildland Provincial Park and the Black Creek Heritage Rangeland were established.

2000 Protected Spray Valley from a major resort development. Spray Valley Provincial Park established.

2003 Influenced twinning plans for the 12.5 kilometre section of the Trans-Canada east of Lake Louise.

2004 Spray Valley and Bow Valley Wildland Provincial Parks were expanded.

2006 Grizzly bear hunt suspended.

2008 Won an Alberta Emerald Award for education program.

2009 CPAWS Calgary/Banff was renamed CPAWS Southern Alberta Chapter.

2010 Grizzly bears listed as threatened species under the Alberta Wildlife Act.

2011 Over 100,000 emails sent to the premier, demanding increased protection of the Castle Special Place.

2011 Stopped Bill 29, which would have undermined Alberta's parks and protected areas.

2012 Logging in Castle wilderness suspended.

2013 Pressured Parks Canada to ensure Sunshine Village's proposed Goat's Eye Mountain day lodge development required to meet national park water quality standards.

2014 Seasonal mandatory travel restrictions were implemented on Bow Valley Parkway.

2014 Influenced South Saskatchewan Regional Plan (SSRP), which increased protection of the eastern slopes.

2015 Environmental education program reached the 100,000 student milestone.

2016 Alberta Recreation Study produced, showing the majority of Albertans participate in outdoor recreation, and support protecting wilderness.

2016 Won the award of excellence for Outstanding Non-Profit Organization for environmental education from the Canadian Network for Environmental Education and Communication (EECOM).

2017 Castle Provincial Park was created, and the Castle Wildland Provincial Park was expanded.

2017 Released the Envisioning a Better Way Forward report, which proposed an ecosystem-based approach to forestry on Alberta's Southern Eastern Slopes.