Individual expenses for elected officials running Stoney Nakoda First Nation reached an all time high of $1.4 million last year, according to financial records quietly released in late November under the First Nations Financial Transparency Act.

The increase in individual expenditures is on top of a two per cent salary increase the politicians received last year and comes as the nation grapples with a larger than expected deficit of $13 million.

It’s the fourth straight deficit the band has recorded since it first began publishing its financial statements in 2014 and not the first time its spending practices have been scrutinized.

In 2015, media reports revealed elected officials were paid a combined $3.3 million in salaries and expenses – a 20 per cent jump from the previous year.

In response, elected officials’ salaries were reduced the following year, however, individual expenses continued to rise jumping by nearly 30 per cent over the next two years to $1.4 million for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2017.

The Stoney Nakoda First Nation is governed by three chiefs and 12 councillors from the Bearspaw, Chiniki and Wesley bands that make up what is known as the Stoney Nakoda Tribal Council.

Among the nation’s three chiefs, Bearspaw Chief Darcy Dixon racked up $204,129 in individual expenses last year, nearly 60 per cent more than the previous year – the most of any politician.

His individual expenses are in addition to his annual tax-free salary of $127,453, which all three chiefs earned last year. Councillors who were elected for the full year earned $91,038 and took home between $5,250 to $139,422 in expenses.

None of the chiefs responded to interview requests, however, acting band administrator Ken Christensen said their wages are fair, explaining each elected official earns a severance package at the end of their elected term, which varies depending on each band.

“I think their salaries and expenses are fair and reasonable,” said Christensen, explaining elected officials are paid three months of salary per year of service at the end of each term.

“If you add the expenses and the wages together, they’re pretty flat. What fluctuates year to year is on how much severance is paid out.”

Despite earning six figure salaries, Christensen described some of the elected officials as “broke.”

“These guys are broke all the time. They don’t actually make that much money. A councillor makes around $90,000 a year, but they’re expected to hand out money when there’s people in need.”

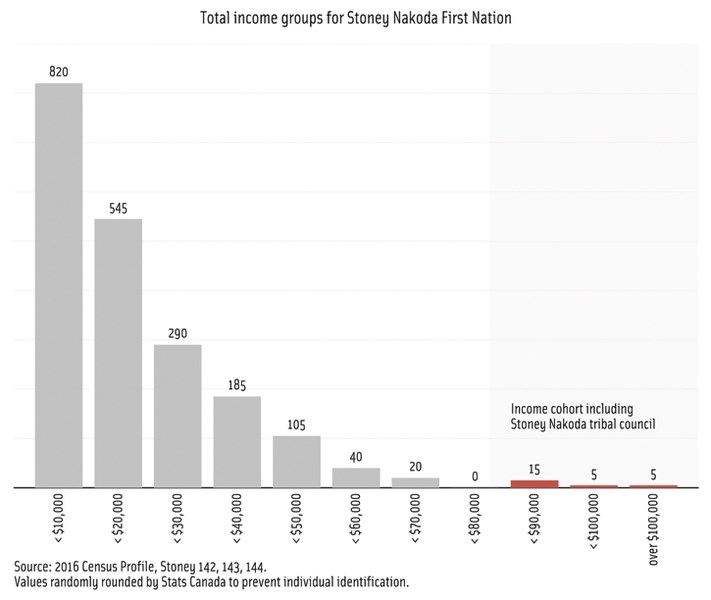

Their salaries stand in stark contrast to the average annual earnings of those living on the reserve, which was an average of $14,488 in 2016, according to the federal census.

“A lot of people don’t work on the reserve or are unemployed and people need to be paid fairly for the position they’re in. These guys are pretty much on call 24 hours a day. I don’t think I could do their job. It would be really tough,” said Christensen.

In comparison to other First Nations communities, the Siksika Nation, located an hour east of Calgary, spent a combined total of $1.2 million on salaries, remuneration and travel expenses last year for 13 elected officials. The highest earner took home a total of $102,000.

“We did some work about two or three years ago and as a percentage of revenues and a percentage of assets, our wages, I think, are right in the middle in terms of First Nations in Alberta,” said Christensen.

John Reilly, a retired provincial court judge who ordered an investigation into the nation’s finances in 1996, said he wasn’t surprised to hear elected officials were reaping the benefits of their position.

“It’s sad,” said Reilly, who has written two books about the injustice Indigenous people face, particularly on the Stoney Nakoda First Nation reserve.

“Traditionally, they say that Sitting Bull never ate until everyone in his band was fed and these people are taking money while a lot of needs in the community are going unmet.”

While individual expenses for elected officials have risen by 30 per cent over the past two years, the combined spending on their salaries and expenses was about $400,000 less than in 2015, when the band faced heavy criticism for its ballooning salaries.

Despite the decrease, the budget still shows the overall cost to support the band’s government increased to $13.9 million from $12.3 million two years earlier.

It’s also not clear where approximately $30.4 million dollars went in an undefined line item called “other expenses.”

The line item is nearly double what was forecast and was the largest annual expense in the budget – ahead of housing at $23.6 million and education at $17.7 million.

Christensen downplayed questions about the figure, pointing instead to the budget’s total expenses, which were approximately $2 million less than anticipated at $131.7 million.

He also blamed the nation’s financial woes on a drop in natural gas prices and its generous social assistance programs.

“The price of natural gas has dropped significantly, so where at one time we were getting $60 million in royalties, we’re not getting anywhere near that much anymore,” said Christensen, adding they have also been working hard to cut expenses.

“Although we’ve cut a lot of expenses, the nation is still pretty generous to its members,” said Christensen.

“Right now they don’t pay for houses, they pay no rent, they pay no utilities, no gas, no electricity, no water and wastewater, there’s no property taxes.”

Questions about its finances follow a commitment by the federal government in December to provide First Nations communities that have a good financial track record with a 10-year grant to pay for things such as healthcare, education and social programs.

The long-term funding plan will be given to 100 First Nation communities to allow them to spend the money as they see fit, giving them greater autonomy over how the money is spent. The program is expected to be implemented by April 1, 2019.

The government has yet to select which First Nations communities will receive the funding, however, according to a speech by Minister of Indigenous Services Jane Philpott, First Nations institutions will determine which communities are ready and willing to participate in the program.

Those that are selected will need to report back to their own members on their priorities and targets.

Christensen said he was confident in the nation’s financial track record.

“All of our federally funded and provincially funded programs, the bulk of course are federal, are in fine shape,” said Christensen.

“If you looked at our education statements or our health statements, we’re not over spending at all on any of those areas. Whatever the government has given us, that’s what we’re spending, or less.”

Reilly said he supported the government’s desire to invest in First Nations communities, but warned that simply writing a blank cheque wasn’t the right approach.

“Non-Indigenous Canada has been living without paying its rent for the last 150 years, so I think billions of dollars to improve the social conditions is called for, it’s owed to them. But giving millions and millions of dollars to tribal governments, which have traditionally just spent it on themselves and done very little for their own people, I think is lunacy.”