BANFF – With the 1877 signing of Treaty 7 and the creation of Canada’s first national park at Banff in 1885, the federal government emptied the Bow Valley region of Indigenous people.

Canadians, Americans and Europeans – white people, really – took advantage of this emptied landscape and began to name and exploit all that the Rocky Mountains had to offer.

Among those individuals were savvy business people, including Byron Harmon, Banff’s first professional photographer, who set up shop and flourished.

Harmon opened a photo studio in Banff in 1906. He later built the Harmon Building, one of Banff Avenue’s heritage buildings.

In his time, Harmon – a founding member of the Alpine Club of Canada and its official photographer – created a unique visual record of Banff and the Rockies in the early 20th Century.

Harmon also photographed First Nations people, primarily members of the Iyethka Nakoda (Stoney Nakoda), at the annual Banff Indian Days. It was the one time each year Indigenous people were generally permitted to enter the park.

And he wasn’t alone. Photographers and tourists alike flocked to the parade route and the meadows at the base of Cascade Mountain with cameras in hand.

While the photographers who attended Banff Indian Days created an extensive photographic record of the Nakoda, how did the Nakoda feel about being photographed?

It’s a question Carole Harmon, who has been surrounded by her grandfather’s legacy since childhood, has been asking herself.

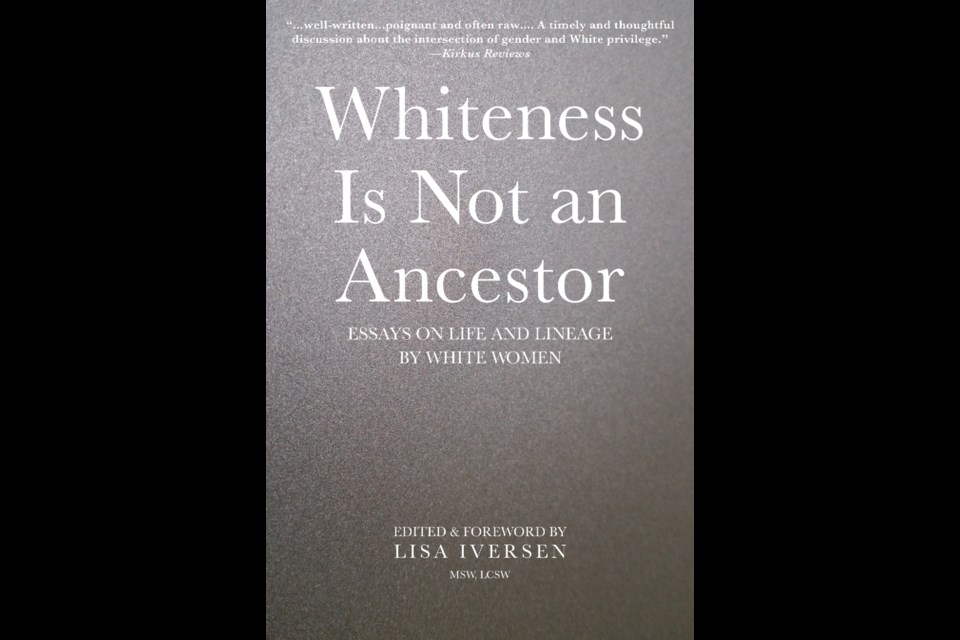

“I’ve been walking with my grandfather all my life. How could I not with his pictures surrounding me every time I visited Dad at work?” writes Carole in her essay in the recently published Whiteness is Not an Ancestor: Essays on Life and Lineage by white Women.

“Among my favourites were a grouping of hand colored portraits of Indigenous people who lived near Banff. As a young girl, I wondered why, in some pictures, people seemed sad or seemed to glare at me?” writes Carole, who was born in Banff.

“Now I have different questions. What did they think of this man who was taking their picture? Did they agree to be photographed? Was he asked to photograph or given permission the subjects didn’t agree with? Always the relationship between photographer and subject is at issue.”

In her essay, In Mountain Light: Walking with My Grandfather, Carole explores her relationship with her grandfather’s legacy (photography and building). She also explores her relationship with photography and the benefit her family has seen from the emptying of the mountain parks of First Nations people.

“The Harmons building supports our family financially, is home to other local businesses, and is a heritage resource within the community,” she writes.

“But what of the people excluded from the parks either by lack of financial means or belonging to a group other than for whom the parks were set aside for?”

In the foreword of Whiteness is Not an Ancestor, editor Lisa Iversen describes “whiteness” as a “powerful fiction” that gives white people “certain privileges from those whose exploitation and vulnerability to violence is justified by their not being white.”

Judging by the 12 essays in the anthology, whiteness often expresses itself in death, hatred, ignorance, judgement, racism, theft, misunderstanding and an advantage based upon skin colour.

Iverson chose white women to write for the anthology, as it often is assumed that they are the victims and not the perpetrators of violence and trauma.

And yet, the opposite is often true.

“Greater understanding, acknowledgement, and visibility of women’s roles in these dynamics are necessary if we are genuine in our desire to bless next generations to more just and peaceful futures,” writes Iversen.

For example, Sonya Lea, a Banff-based writer whose family has deep roots in Kentucky, explores her family’s connection to the 1936 lynching of a young black man, Rainey Bethea, in her essay, Bloodlines: A Legal Lynching and a Family’s Reckoning.

An all-white jury found Bethea guilt of raping a white woman and sentenced him to die by hanging in the last public execution in the U.S.

Lea’s grandmother inserted herself into the events by claiming that she had tipped off police to the location of jewelry that Bethea had supposedly stolen. Her great-grandmother’s cousin, Herman Birkhead, meanwhile, served as the prosecuting attorney for the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Birkhead made moves to ensure that Bethea died by hanging.

In her essay, Lea chronicles Bethea’s story while confronting her own and her family’s racism.

“For too long I wanted to deny the racism of myself and my ancestors,” she writes.

“White people tend to imagine that anti-racism work is difficult and shameful. But there’s a dignity in allowing our guilt to be witnessed, in claiming the perpetrator, and enhancing our ability to face the consequences of our actions.”

It takes courage to crack open a family history with a critical and objective eye, as both Carole and Lea demonstrate. Doing so leads to an inevitable confrontation with the past and the role our ancestors played.

In Carole’s case, her questions about her grandfather’s legacy do not diminish what he accomplished. Instead, by looking critically at the time Harmon became established in Banff, it reminds us of how Canada’s racist policies affected the First Nations people of the Rocky Mountains.

“My grandfather documented a passing way of life, one he both participated in and commented on,” writes Carole. “In his nature photography, he exaggerated the narrative, purposely choosing situations to heighten the dramatic effect. When I turn again to his portraits of Indigenous individuals, I see the same thing. They were part of a larger story of a world which had vanished with the rapidity no one should overlook. The theme of wilderness adventure was romanticized. Its effect on Indigenous peoples was devastating.”

Whiteness is Not an Ancestor: Essays on Life and Lineage by white Women, was released by the Center for Ancestral Blueprints Publishing on Oct. 13.

Join Carole Harmon and fellow essayist Pam Emerson Nov. 20 at 2 p.m. for a conversation moderated by Devyani Saltzman, who was previously the director of literary arts at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Event information available at www.cab-publishing.com.