The Canadian government has a long history of failing its veterans.

Regardless of the government of the day, the ability to address homelessness, addiction issues and suicide among veterans and active service personnel has been shameful.

In the past 10 years, the Armed Forces have had 191 members take their own lives, which is 33 more than the 158 personnel who were killed during Afghanistan combat mission between 2001-14.

While there are supports available, the struggle to access them is onerous and when people begin receiving them they are working with government employees who themselves are understaffed, under-resourced and overwhelmed.

Case managers at Veterans Affairs Canada have publicly stated their caseloads are overwhelming, leading to less focus on people who need greater attention in addressing concerns such as post-traumatic stress disorder or adjusting to civilian life.

When the Stephen Harper Conservative government left power, the ratio had reached 40 veterans to each case manager due to significant and many cuts to programs.

After being elected in 2015, the Justin Trudeau Liberal government aimed to get the number to no more than 25 veterans per case manager.

Veterans Affairs reports the ratio is 33 to one, but many have more, and at times upwards of 50, according to the Union of Veterans’ Affairs Employees.

An internal review in 2019 found case managers spent more time filling out paperwork than actually helping veterans. The review noted veterans who received attentive help from case managers had better physical and mental health.

Though programs exist, it’s often a fight to access the services.

Many veterans are all too familiar with working several years to get on a list to receive financial support or counselling.

Of the more than 40,000 Canadians who served in Afghanistan, roughly 17 per cent in 2019 received federal help for psychological trauma after being diagnosed with PTSD, according to access to information files obtained by the Canadian Press in 2019.

The Department of National Defence and Statistics Canada work together to now release an annual veteran suicide mortality study. It analyzes data from 1976 onwards on veteran suicide.

The annual study began in 2017 after several years of Canadian Armed Forces leadership pushing back against growing evidence that members of the military have a higher risk of suicide than the general public.

In June, the Canadian Armed Forces stated 16 service members died by suicide in 2020. In 2019, it was 20.

A suicide prevention strategy for military members and veterans was introduced in 2017, promising to improve services and support, but it also been slow to implement recommendations.

Homelessness and addiction have plagued Armed Forces veterans after they leave service.

Unfortunately, there are no specific statistics for the number of homeless veterans, but estimates have been placed it between 3,000 to 5,000.

A 2018 survey of emergency shelters in 61 communities found 4.4 per cent of people using the services were veterans, with only about 1.5 per cent of the Canadian population being veterans.

A 2019 House of Commons committee concluded veterans are more apt to experience issues with alcohol and drugs and a loss of identity after leaving the military and attempting to re-enter civilian life.

The committee made 10 recommendations from rent supplement to specific funding for housing projects aimed at veterans. Few recommendations have yet to see the light of day.

Where the government has failed, grassroots organizations have attempted to fill the gaps.

Cadence is a health centre in Newmarket, Ont. to help veterans and first responders, Wounded Warriors provides month health supports to veterans, first responders and their families, Veterans Transition Network is a national charity assisting veterans with mental health services and the Canadian Afghanistan War Veterans Association offers support and camaraderie to thousands of veterans.

Their efforts are needed in helping the veterans not receiving help from the federal government agencies.

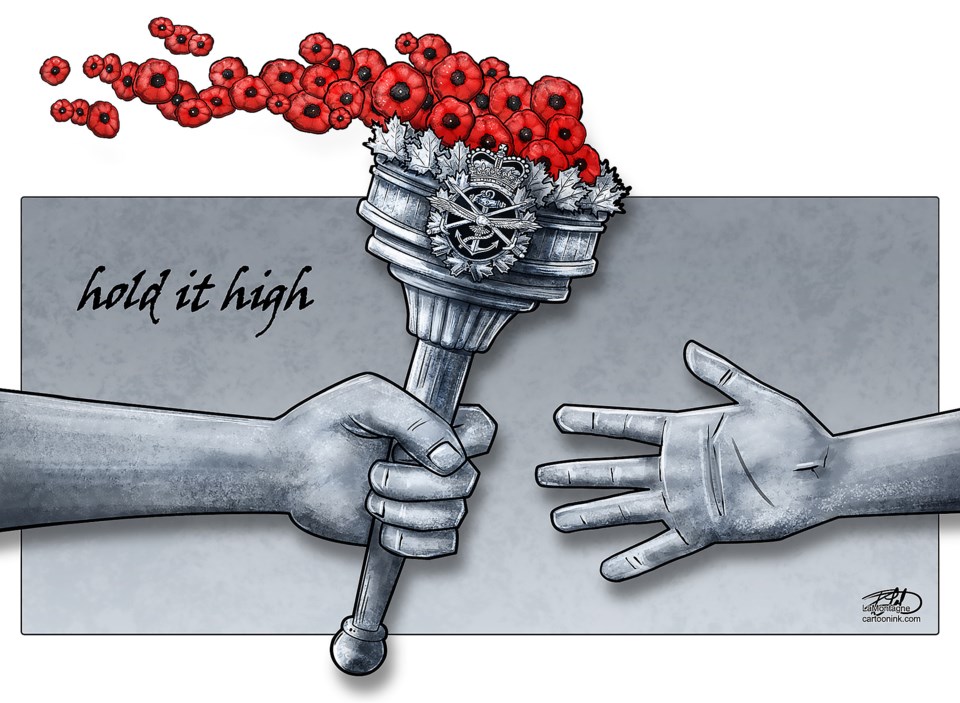

It is imperative for citizens to push their elected representatives to do more. People stop and take pause each Nov. 11, but the issues veterans face are year round.

While we remember the battles fought of previous wars and sacrifices made, the fight is still ongoing to help veterans.