BANFF – Inuvialuk Angus Cockney found his freedom trail on the open tundra.

It was residential school that took his freedom, and residential school, where he fell in love with cross-country skiing, that gave it back.

“I started cross-country skiing when I was six. I was skiing for the need to feel free; to set abound,” said Cockney. “I wasn’t weak; I was strong. I wasn’t a loser; I was a winner.

“That was a way for me to stay on that path.”

Cockney, who spent 13 years in a Catholic-run residential school in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, 150 kilometres south of his home in Tuktoyaktuk, also acknowledges the physical and mental abuse that went on there.

But on his own path to reconciliation, he’s forgiven the system which inflicted pain upon him. When he looks back on the experience, he credits it with shaping him into the man he is today – a former competitive skier; a father; an artist.

“It’s all about making choices. … There’s a lot of adversity in that life, in that experience. But it’s not about how you make it, it’s how you take it,” he said.

At eight years old, Cockney was orphaned. It was in residential school he learned his mother, father and three siblings died in a house fire back home.

“When you talk to each survivor up there, you get all kinds of stories, and my story is one, of course, of adversity, but also perseverance,” Cockney told a packed house at The Banff Centre's Margaret Greenham Theatre on Friday (Sept. 29).

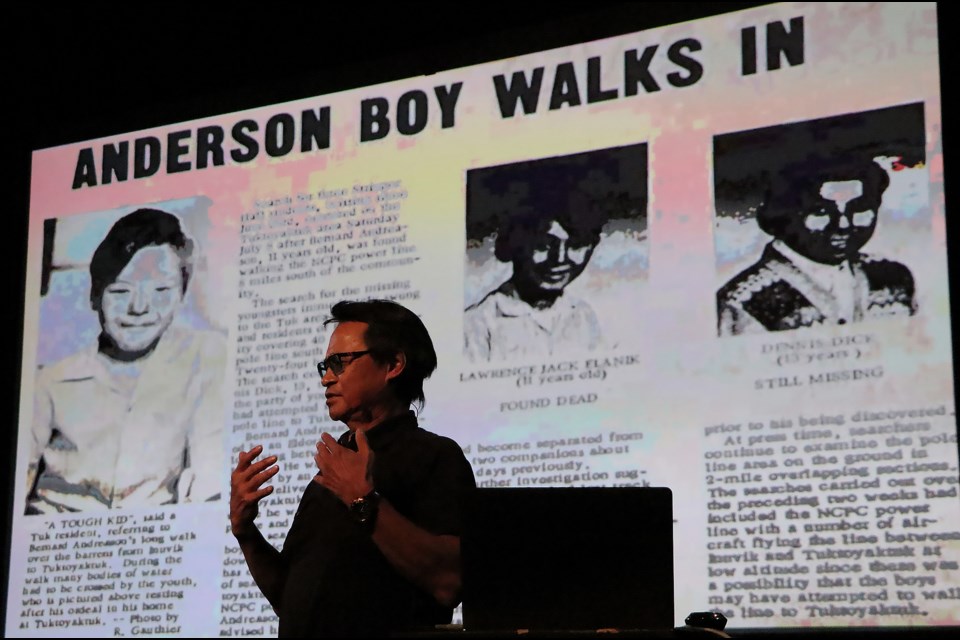

A news article blown up across the screen behind him, the Inuvialuk man, who moved to Canmore in 1979, told the story of three boys who ran from the very residential school he attended, in June 1972.

Bernard Andreason, Lawrence Jack Elanik and Dennis Dick, aged 11 to 13, left the institution in Inuvik on a journey home to Tuktoyaktuk, but only Andreason survived the harrowing journey on foot.

Cockney uses the story as a metaphor for his own life.

“Only Bernard made it back to town,” he said.

With a determined spirit, Cockney, now in his mid-60s, was able to find a silver lining in life in cross-country skiing. To this day, he keeps a firm grip on his poles.

Father Jean-Marie Mouchet, a legend of cross-country skiing in the north who introduced the Territorial Experimental Ski Training (TEST) program, played a pivotal role in Cockney pursuing the sport competitively.

The program ultimately helped lead former residential school students and twin sisters, Sharon and Shirley Firth to compete in the 1972 Olympics, among others.

It was Mouchet’s belief in Cockney to be great that lit a fire inside the young Inuvialuk.

“Here I am inspired, and guess what? I think I found my own freedom trail,” said Cockney, who went on to become a junior national champion in cross-country skiing in 1973, '74 and '75.

“It’s the incredible feeling on skis out there on the tundra, the freedom, the north wind, hearing yourself breathing outside of that structured environment.”

One of the primary colonial effects contributing to the elevated rate of suicide and addiction among Indigenous people is inter-generational trauma, much of it from residential schools.

Cockney has experienced much trauma and is always aware of the weight, but he's found a way to lift it in knowing his children, influencer and actress Marika Sila, and Jesse Cockney, an Olympic cross-country skier following in his father's footsteps, are on their own freedom trails.

He also makes a point of getting on his skis as often as he can.

“I’m always trying to maintain that feeling; that relationship with myself and on the land,” Cockney said. “It’s still there; the freedom trail will always be there.”

The Local Journalism Initiative is funded by the Government of Canada. The position covers Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation and Kananaskis Country.