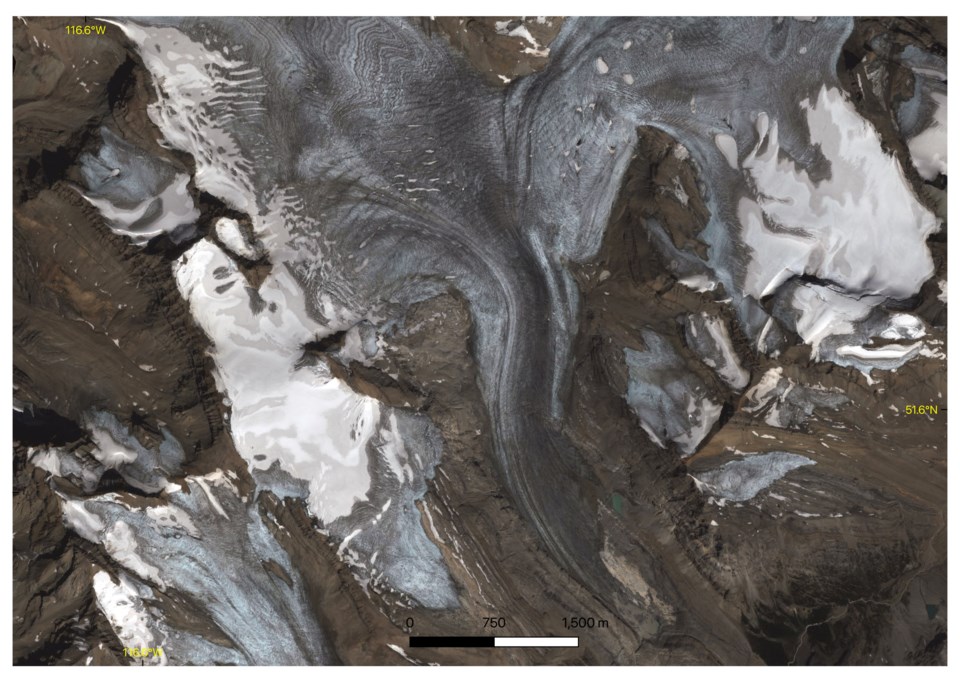

BANFF – The Saskatchewan Glacier in Banff National Park melted this year at a rate never before seen – up to 10 metres on some parts of the glacier.

The alarming discovery was made by a team of researchers, including glaciologist Brian Menounos, using technology known as laser altimetry operated from an airplane to measure elevation changes of glaciers.

“Certainly many of the lowest elevations on the glacier did lose up to 10 metres in places,” said Menounos, professor of earth sciences at the University of Northern British Columbia and Canada research chair in glacier change.

“What is clear, based on earlier surveys, is that we haven’t seen that degree of melt we’re experiencing now ever before.”

The researchers have been surveying the Saskatchewan Glacier, a toe of the Columbia Icefield, as well as hundreds of other glaciers in Canada’s Rocky Mountains, twice a year since at least 2017.

Peyto Glacier in Banff National Park and Yoho Glacier in Yoho National Park near Field, B.C., both outflow glaciers extending from the Wapta Icefield, experienced similar unprecedented melts this year. These glaciers have been part of Menounos' work since 2015.

“We noticed extensive melt on others and the magnitude of that melt increases as you move southward,” said Menounos.

To quantify the health of glaciers, or what’s called the net balance of the glacier, the researchers measure the difference between the snow accumulated over winter and the snow and ice melted over the summer.

“Just like a bank account, you can actually deposit money or take it out,” said Menounos. “Unfortunately, for the last number of years, most years have been a net loss.”

To do the study, a laser altimeter instrument emits short flashes of laser light, which travels to the surface of the glaciers from an aircraft. It measures the round-trip time of the light pulse to get the distance between the glacier surface and the receiver on the plane.

“You’re shooting tens of thousands of photons – energetic light from the laser – and they are digitally encoded so if you know the position of the aircraft you can figure out how long it takes the laser light to come back to the receiver,” said Menounos.

“Thereby, you can determine the elevation below the aircraft, and if you do this repeatedly, then you can see how that elevation changes, and in the case of the Saskatchewan Glacier or the many glaciers that we visit in the Rockies, we can actually see the loss over time.”

The data collected is still being crunched for a peer-reviewed paper, but the researchers believe a number of factors contributed to the rapid melt this year, including extreme temperatures across western Canada earlier in summer.

Banff obliterated temperature records on six consecutive days, recording its hottest day in recorded history on June 29 as the mercury soared to 37.8 Celsius. That smashed the previous record for that day of 33.9 C in 1937 and the all-time Banff high of 34.4 C on July 17, 1941.

In the mountains, temperatures cool down about 1 C with every 100 metres of elevation gain. In addition, June is typically the wettest month of the year, but this year was much drier than usual, recording 24 mm of rainfall this year compared to an average of 62 mm for that month.

Menounos said the exceptionally dry weather – the so-called heat dome – also coincided with the summer solstice, a time of year when daylight hours are the longest in the northern hemisphere.

“We had the most sunlight on the glaciers and this is important because if you want to melt snow and ice, it’s not just the sensible heat – that is, the temperature we can feel – but it’s also the energy that comes in from sunlight,” he said.

“It was also an above average summertime temperatures, so when you put all that together – warm, dry conditions, early season extreme melt – then you’re really setting up for a long summer of melt.”

The mounting evidence of climate change on glacial recession is crystal clear.

“Clearly the ice is responding to a temperature imbalance and an energy imbalance,” said Menounos, noting in the short-term the melting ice pumps a lot of water into the Saskatchewan River.

“Unfortunately, that’s not a component that’s going to be replaced and that’s a component of flow that we refer to as glacier wastage. That’s ice that is melting that very unlikely be replaced in the decades ahead.”

Even under moderation emissions scenarios, Menounos said most of the glaciers in the Rockies will be gone by the end of the century.

Not only do glaciers nourish many of the headwater streams, but he said they are also a cultural legacy and matter to Indigenous peoples.

In addition, he said the loss of glaciers in the Canadian Rockies will impact tourism in the decades to come.

“Not having those glaciers is going to change the landscape not just for people living there, but also for people coming to the Rockies, for example, to be on the Icefields Parkway,” said Menounos.

“What will it be like at the end of the century for tourists? There will be beautiful mountains, but unfortunately, there’s predicted to be not a lot of ice left.”