BANFF – Bones are proving crucial to understanding the lives of ancient bison in Banff National Park.

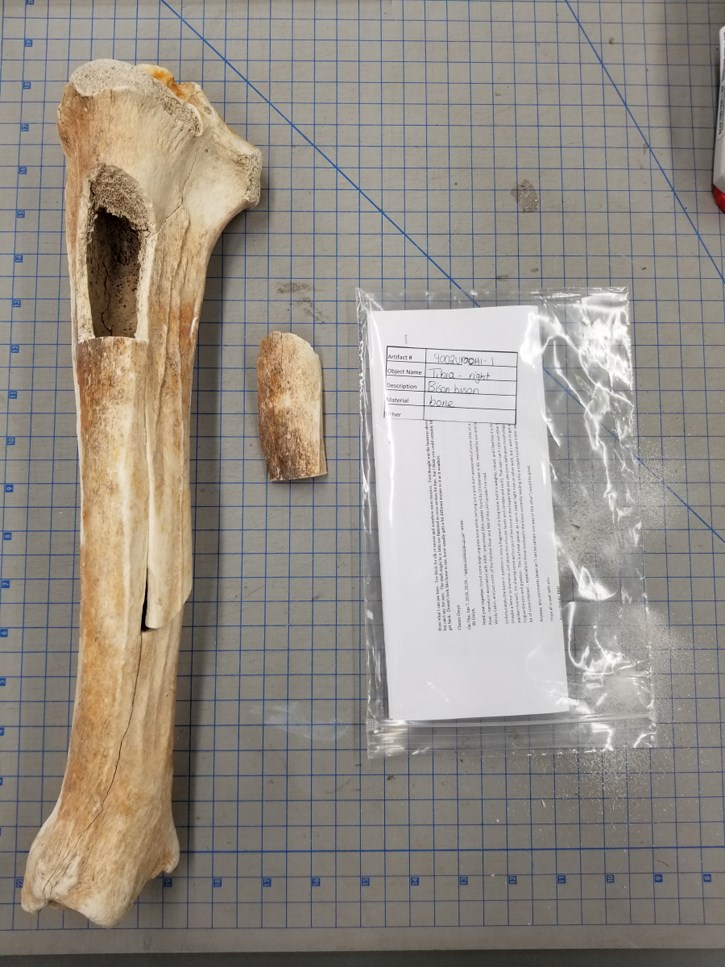

A 2,100-year-old copper-coloured bison bone found along Brewster Creek west of the Banff townsite forms part of a growing body of evidence suggesting some plains bison spent most, if not all of their time in the mountains before the species almost went extinct.

Recent radio carbon dating of about 15 bison bones revealed the age of the bones, while another test known as isotope analysis sheds light on the historical habitat and diet of bison, providing clues as to where bison historically spent their time.

Parks Canada officials say by comparing the carbon and nitrogen ratios stored in the bone collagen, researchers estimated the ratio of mountain grasses versus prairie, which provided more evidence that their historic range included the mountains.

“It’s suggesting that these particular individual bison could have gone out of the mountains a little bit, but not very much,” said Karsten Heuer, manager of Banff’s bison reintroduction project.

“It’s at least not saying that these guys were outside on the prairies all the time, and we happen to be finding remains of bison that were only in mountains for a few days and were lost.”

This is good news for the $6.4 million bison reintroduction project, which involved bringing 16 plains bison from a disease-free population at Elk Island National Park to Banff’s backcountry in 2017 – the first time bison were in Banff’s backcountry in 160 years.

For the first 16 months, bison were held in a fenced pasture in the Panther River Valley in an attempt to anchor them to their new home before their release into the greater 1,200-square-kilometre reintroduction zone in July last year.

Two bulls almost immediately bolted onto provincial lands, leading to the destruction of one and relocation of the other, which was a blow to the five-year pilot project in its very early days.

With cows successfully breeding for the past two years, the 34-member herd is currently made up of four bulls, 10 cows, 10 yearlings and 10 calves, and more calves are expected any time now.

For this reintroduced herd, Heuer said the most recent results from bison bones spell good news for the future.

“What we’re trying to reintroduce is a missing component of a past ecosystem … we definitely know that it’s possible for these bison to live here,” he said.

“Whether or not these specific animals that we’ve reintroduced will stay here long-term … it’s certainly suggesting that’s the case. They’ve survived their first winter looking healthy, but we’ll see.”

Other than the two bulls that hightailed it out of the park, the rest of the herd has stayed within the reintroduction zone, although they sometimes bounce off the fences, particularly at the Red Deer River boundary.

The fences were put in strategic locations to deter bison from leaving the reintroduction zone, but allow other species to move freely.

“It’s nice that these bison have an inherent respect for fences,” said Heuer, adding the initial 16 members of the herd came from Elk Island, which is a fenced national park about 35 kms east of Edmonton.

“What we’re trying to do is set a pattern that hopefully will be passed on from generation to generation. It’s not unlike conditioning a bear to avoid campgrounds and highway roadsides, with the idea that hopefully they’ll pass that behaviour onto their offspring.”

Bison remains have been found throughout Banff National Park, including bone fragments found at prehistoric campgrounds uncovered near Lake Minnewanka dating back approximately 10,370 years, as well as 9,300-year-old bone fragments at Vermilion Lakes.

It was Parks Canada staff who stumbled across the large bison bone on a gravel bar at Brewster Creek last spring. With GPS, they recorded the location before taking it to Parks Canada’s terrestrial archaeologists for examination.

Heuer said that following a prescribed fire in the Panther River Valley, a team of archaeologists last year uncovered a 660-year-old bone in the soft release pasture where the reintroduced bison herd was initially held.

He said these bone tests confirm that bison occupied a variety of habitats in Banff National Park, including at high elevations such as the 2,000-metre Elkhorn Pass within the bison reintroduction zone.

“When we found the bison that we released up on mountain ridges and in the alpine last summer, there actually is archeological evidence for them having done that in the past,” said Heuer.

As the reintroduced bison herd wallows, breaks trails and grazes, Heuer said the animals are actually uncovering past evidence of them being here hundreds or thousands of years ago in terms of old wallows.

“I think it’s pretty neat when the project in modern day is actually uncovering affirmation of their presence historically,” he said.

Millions of bison, estimated as high as 30 million at one time, roamed the plains of North America before overhunting edged the species to the brink of extinction in the 1850s.

The last wild bison in Banff is believed to been shot near Lake Louise in 1858 by James Hector, a geologist appointed to the Palliser Expedition to find new railway routes.