MD OF BIGHORN – There are two sides to every story as the saying goes.

Reality, however, suggests there are many sides.

Louis Marret embarked on a journey to Canada from France in 1898 without a penny in his pocket. About 24 years old at the time, his first known address in the Great White North was in Canmore.

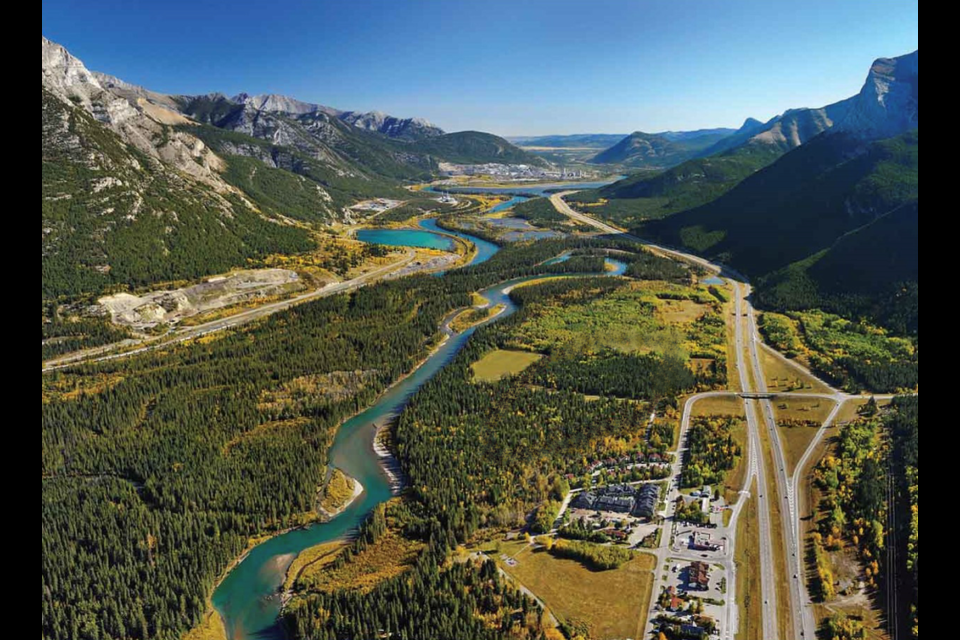

Joined by his older brother Jean Marret on the westward voyage, in 1902, their youngest brother, François Marret, also moved to work on a small dairy farm the brothers had established on the flats where Pigeon Creek enters the Bow River. They also worked in the coal mines in Canmore.

“Three boys [with] numerous years [in the] army, decided to leave towards Canada to participate in the gold rush,” said Yvette Guilhem, a family researcher and distant second cousin, once removed of the Marret brothers, in an email.

The three brothers arrived in the Bow Valley with meagre resources and dreams of a better life. But despite their shared ambition, only Louis went further north to the Yukon and struck it rich – and he struck it big.

An article printed in the Dawson Daily News May 11, 1906, reported he discovered gold at Baker Creek on the Stewart River during the Yukon’s Klondike gold rush.

“It is estimated there will be 300 men working on Baker next winter,” the article stated. “On discovery claim, owned by Louis Marret, fine pay has been obtained. The claim is not for sale, and rich pans have been taken out. Occasionally fine nuggets are found.”

Between January 1905 and May 1906, it’s believed Marret earned $420,000, said Dene Cooper, former MD of Bighorn reeve and co-author with former Rocky Mountain Outlook journalist Rob Alexander of the 712-page historical book Exshaw: Heart of the Valley. In today’s money, that’s about $18 million.

Cooper, who is deeply entrenched in Bow Valley history, was aware of only two Marret brothers – Jean and François – at the time of publishing the book in 2005. That was until Guilhem reached out from half a world away.

“It reignited a great mystery about their becoming since their departure towards the USA and Canada,” she wrote to Cooper in an email.

“Finally, thanks to the name of Dead Man’s Flats, I knew the sad end of the history.”

To Bow Valley locals, the Marret name may sound familiar.

In the early morning hours on May 11, 1904, François brutally murdered Jean in his bed at the dairy farm with an axe, then dumped his brother’s body into the Bow River.

The youngest brother told a jury trial he committed the act because he believed Jean was planning to kill him with an electrical machine he heard in the forest on multiple occasions, but never saw.

He also told the court the act was ordered by their dead parents because Jean refused to pay him for working at the dairy.

He was arrested by North West Mounted Police at Canmore’s Oskaloosa Hotel that morning after reporting to the mines why Jean would not be at work that day. François was found guilty of murder by a jury trial but later was acquitted of his crime on account of insanity.

In 1909, he died at the Brandon Asylum in Brandon, Manitoba, where he was committed.

The hamlet that would later occupy the area where the Marret’s lived officially became known as Dead Man’s Flats in 1985.

Cooper said it’s not clear exactly when the name Dead Man’s Flats was coined, but it was commonly used before it changed from Pigeon Mountain Service Centre – its moniker from 1974-85.

The (Îyârhe) Stoney Nakoda First Nation also tell of how the area got its name, rooted in a story of Stoney trappers feigning death to avoid trouble with a national park warden, which had jurisdiction over the area as part of Banff National Park until 1930.

Cooper said it’s a wonder if the origin of the name Dead Man’s Flats indeed stems from the brothers’ history, and whether its unique naming would have taken a different turn, or whether a murder would have still occurred if the eldest Marret brother had stayed in the Bow Valley, or had they all followed their dreams for gold.

There is no record of Marret returning to the area after the murder. However, Guilhem traced a move to Washington state after 1911 through genealogical records, where he married twice and enlisted in the United States Army as a field artillery officer, but the First World War ended before he was deployed.

By all accounts, this was not someone who had $18 million to their name, Cooper noted.

“He worked at many jobs. I can’t say that he’d look to have $18 million in his back pocket. So, I don’t know why he moved or where the money went,” he said.

Guilhem said the brothers also had a younger sister, Eugenie Marret, who kept in touch with her only surviving brother by letter from France.

“I think that he told the truth on the drama because [both] gave up having children of their own blood,” she said.

Instead of each having their own children, they adopted.

“It seems they saw insanity on both sides of the family and in those days, they considered culling the herd, or eugenics. So, it looks that both of them decided in their lives not to have children themselves,” said Cooper, noting there are many parallels that can be drawn from the brothers’ tumultuous journey seeking fortune and opportunity for other families.

“Louis had gone up north prospecting, François arrives clueless about organizing his own life and Jean is the responsible older brother,” he said.

“François comes on the scene after his brother Louis has left, and the guys down here are just going through daily life, with François dealing with a distorted story of interpretation within his own mind and without the proper care to deal with that. So, I think there’s a story about families challenged by mental disorder.

“And then there was greed involved; they all came out hungry for bucks. All of us have been touched by things that this family was dealing with.”

Cooper said the idea behind Exshaw: Heart of the Valley was to unveil more stories.

“We don’t have to tell all the story. But we have to keep people understanding people, place and time,” he said.

The Local Journalism Initiative is funded by the Government of Canada. The position covers Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation and Kananaskis Country.