BANFF – Bruce McLellan estimates he’s captured and collared hundreds of grizzly bears over the past 43 years in his bid to better understand what makes this iconic species of the Canadian wilderness tick.

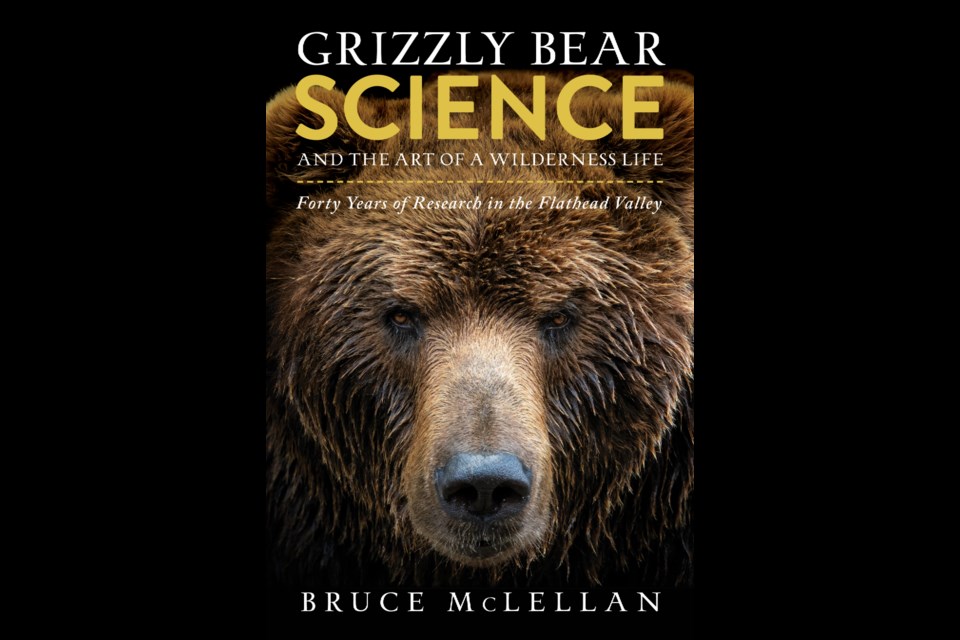

In his first ever book, Grizzly Bear Science and the Art of a Wilderness Life: Forty Years of Research in the Flathead Valley to be published by Rocky Mountain Books on Nov. 7, McLellan seeks to bridge the gap between what is known by the general public and what is known by scientists about grizzlies.

Following the lives of hundreds of grizzly bears, many from birth all the way to their death in their late 20s or 30s, he kicks off the book with a riveting story about his first grizzly bear capture – a 600-pound male with a neck that was 36 inches in circumference – in 1978 in the Flathead Valley, which straddles the B.C.-Montana border.

As rookies, he and cowboy Joe Perry, both in their mid-20s, had snared the bear, and despite several darts loaded with drugs fired at the big brute – a drug that was safe over a wide range of doses – the grizzly wouldn’t go to sleep.

Each time the two men approached, the grizzly would do a series of “powerful charging rushes” towards them, forcing them to race back to the safety of the truck. Their theory was the bear was simply too fat to allow the drugs to get into the bloodstream.

Eventually successful in getting a collar on the bear, they called him Rushes following the adrenaline-pumping experience.

“When you get that little shot of adrenaline, when you encounter a large carnivore close up like that, boy, it makes you feel wonderfully alive,” said McLellan in an interview with the Outlook.

McLellan tracked the big bear from 1978 to his death on May 11, 1981, when he found the radio collar in the hands of a hunter.

The bear had been shot, either by an American who had crossed the border illegally, or his Canadian hunting partner who had a permit. McLellan suspects it was the American hunter who made the fatal shot because the three-metre bear rug ended up in the U.S.

“I’m sorry, old buddy,” he wrote in his book, reliving the experience of standing by the bear’s lifeless body as he blinked back tears. “Life isn’t really fair, is it?”

McLellan’s 304-page story of grizzly bear behaviour and ecology is based on dozens of research papers he’s had published, which are based on the actual lives of more than 200 grizzly bears radio-collared in the Flathead and hundreds more elsewhere during his 40-plus years of research.

The scientific chapters cover topics ranging from the bears’ diet and how it influences changes in body fat and muscle, to how bears are counted and factors that influence births and deaths and regulate population size, and impacts of roads and seismic lines on populations.

Mixed among the science chapters is the story of how McLellan and his wife Celine began the Flathead grizzly project, built a log cabin on the banks of the Flathead River, and raised their two children – Michelle and Charlie – in the wilderness among bears, wolves, and cougars. The family endured floods that washed away part of their camp and forest fires that burned thousands of square kilometres.

McLellan, who now lives in D’Arcy, B.C, didn’t start out his distinguished career in grizzly bear research, but initially worked on elk and mountain goat projects.

It was the late 1970s, and a giant controversy was brewing over conservation of grizzly bears in the Flathead Valley, adjacent to Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, and what planned roads, logging and development for oil and gas would mean for bears.

“The wildlife managers were fairly concerned about logging and grizzly bears,” he said.

“It was kind of ‘do you want to do a grizzly bear study?’ so it was that or unemployment.”

McLellan’s career included a stint as president of the International Association for Bear Research and Management and co-chair of the IUCN Bear Specialist Group. He is currently the Redlist authority for this group of international scientists

Besides research, he has been involved with many land-use, access management, and recreation management policy processes and, with others, initiated the Bear Awareness Society in the 1990s that evolved into Wildsafe BC.

Coexisting with grizzly bears into the future, said McLellan, will be an increasing challenge and will require a deep understanding of these large carnivores.

“People killing bears was and continues to be by far the dominant way they die, in almost all ecosystems. Humans dominate their lives. That’s the way they die,” McLellan said.

“If we want to keep them around, which I think the greater public is demanding, we’re going to have to live with them. It’s just going to take changes in attitude and tolerance.”

Ultimately, McLellan said grizzlies are driven by high-energy food, particularly in fall, whether it’s huckleberries, buffalo-berries, salmon or whitebark pine seeds, depending where they live.

“If you’ve got an area with any of these higher energy foods, you’ll get an abundance of bears, near human settlements or even where there’s a lot of backcountry use,” he said.

“There’s ways you can really reduce any chances of issues, but, of course, you won’t entirely eliminate them, and we found that out with the event in Banff National Park.”

McLellan was referencing the recent fatal grizzly bear attack in Banff National Park in Red Deer River Valley of west of Ya Ha Tinda Ranch on Sept. 29.

Doug Inglis and Jenny Gusse, both 62, from Lethbridge, who managed to deploy one can of bear spray, were killed in the attack as was their border collie.

A necropsy – a post-mortem examination on an animal – revealed the grizzly was an under-nourished 25-year-old female, with teeth in poor condition and less than normal body fat for this time of year.

McLellan speculates there may have been some background influence that had nothing to do with the couple, such as the bear getting into food scraps in a campfire, for example, elsewhere in the hours or days leading up or the mauling.

“There might have been something else going on an hour or two before that got the bear agitated, and then maybe just hearing the dog barking in the tent or whatnot set it off,” he said.

“I do ponder why after so many years, all of a sudden she flipped her behaviour and did something so radically different. We’ll never know. We could speculate but we’ll never know.”

McLellan stresses fatalities and contact bear encounters are extremely rare.

In fact, over the last 10 years, there have been three recorded non-fatal, contact encounters with grizzly bears in Banff National Park, all a result of surprise encounters, and there hasn’t been a fatal bear mauling in Banff in decades.

“It’s actually somewhat amazing that there's so many people out there hiking and fishing and hunting and camping and doing all this stuff, and yet events are very, very rare,” said McLellan.

“It’s not the most dangerous thing we’re dealing with in our lives, that’s for sure.”

Not only do bears bump up against people and communities, but McLellan said they deal with wolves and with other bears, too, noting something can tip them off once in a while and get them really revved up.

“Bears are living a complex life out there and we never know what really has been going on in their life,” he said.