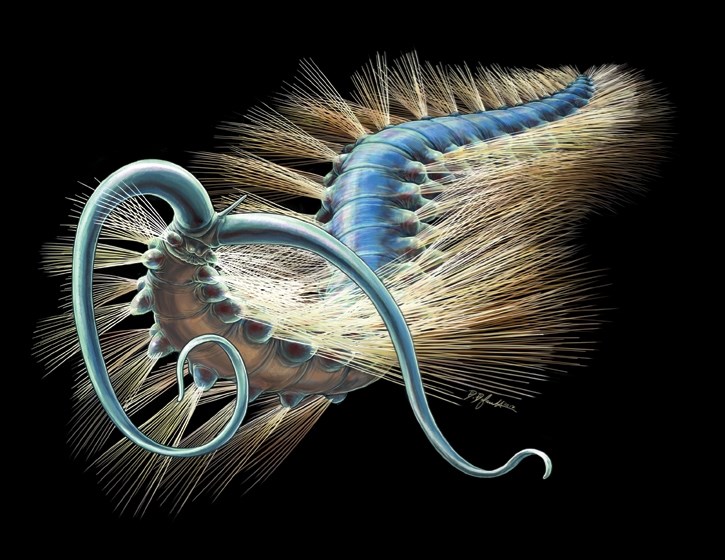

Fossils of an ancient bristle worm discovered in a band of 508-million-year-old shale in Kootenay National Park have allowed paleontologists to dig into the evolutionary origins of a group of worms known as annelids.

Annelids, or segmented worms, include leeches, earthworms and marine worms such as modern bristle worms. And, while annelids are one of the world’s success stories with species numbering in the thousands, their early evolution has always been something of a mystery.

Writing in the January issue of the scientific journal Current Biology, Karma Nanglu, a University of Toronto (U of T) PhD candidate and researcher at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), and Jean-Bernard Caron, an associate professor at U of T and the ROM’s senior curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology, explain that the recently discovered Kootenayscolex barbarensis is not only a new species, but one of the most abundant and best-preserved species of annelid found among the fossils at a Burgess Shale site located near Marble Canyon.

Cambrian Period Burgess Shale fossils are known for their exceptional preservation, and Kootenayscolex is no different. Excavated mostly at the Marble Canyon site, some of the 500-plus fossils of this extinct worm, which range in size from 1 mm to 3 cm, show details never seen before in a fossilized annelid, according to Caron. These features include internal tissue and what might be nervous tissue.

“(This) is the first time we see evidence of such delicate features in a fossil annelid. This exceptional preservation opens a new chapter in the study of these ancient worms,” Caron wrote in a media release from the ROM.

The worms, like all the creatures of the Burgess Shale, were entombed by mud flows that poured into the Cambrian seas.

Nanglu and Caron believe Kootenayscolex would have been active in the sediment along the bottom of the sea, eating bits of organic material.

The exceptional preservation, which Caron described as exceedingly rare, allowed researchers to suggest that the shape and structure of the annelid head evolved from its segmented body.

Bristle worms, including Kootenayscolex, are known for the fine bristles found along their bodies, some of which were likely used for defense. But unlike living bristle worms, Nanglu points out that what makes Kootenayscolex interesting is the bristles located around its mouth.

“This new fossil species seems to suggest that the annelid head evolved from posterior body segments which had pair bundles of bristles …,” said Nanglu.

In the study, the authors indicate that more fossils of Kootenayscolex are needed to corroborate their hypothesis.

Kootenayscolex barbarensis was named for where it was found (Kootenay National Park), Greek for worm (scolex) and after Barbara Polk Milstein, a ROM volunteer and supporter of Burgess Shale research.

A New Burgess Shale Polychaete and the Origin of the Annelid Head Revisited was published in Current Biology on Jan. 22.