American explorers Lewis and Clark, led by their Shonshone guide Sacagawea, spent nearly three years exploring the American West.

When they returned to Illinois in 1806 at the end of their journey, they were acclaimed as heroes and they’ve been celebrated as such since then.

The result is this American duo – along with Sacagawea – are well known, even in Canada, which is not surprising, but it is disappointing given that Canada can boast an even more remarkable duo in Charlotte Small, a Métis of Cree and Scottish heritage, and her husband, explorer and fur trader David Thompson.

Thompson is a relatively known figure; his remarkably accurate maps were used as the basis for subsequent maps of the West for nearly a century. Thompson made the CBC’s list of Greatest Canadians, but came in at 73, whereas hockey loudmouth Don Cherry bellowed his way to No. 8.

Small, meanwhile, who frequently travelled with her husband and often with children in tow, is a lesser-known figure, as women in recorded history tend to be. In her lifetime, Small travelled over 40,000 kilometres – 3.5 times further than Lewis, Clark and Sacagawea. And yet Canadians are apt to know more about Sacagawea.

But with Small’s recent designation as a person of national historic significance, that may change.

In honour of her contributions to the fur trade and exploration of Western Canada, and the role Aboriginal women played in the building of Canada, Small has been named a person of national historic significance by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, established and supported by Parks Canada.

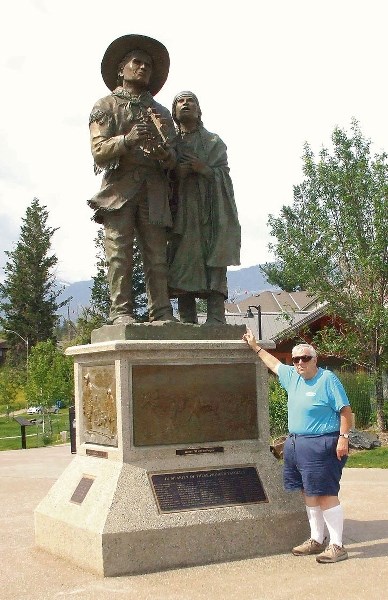

The board installed a commemorative plaque at Rocky Mountain Historic Site on Canada Day to mark the occasion.

Greg Joyce, site manager at the Rocky Mountain House National Historic Site, said the story of Small and Aboriginal women in general are told in all of the site’s programming and displays, including daily programs.

But declaring Small a person of national historic significance allows the historic site to add one more layer.

“It allows us to bring attention to the importance that women did play in the fur trade and Aboriginal women as well and it supports the larger story of not only the fur trade, but westward expansion,” he said. “The fort was here to support the fur trade and westward expansion and their first child was born here as well.”

Small was born in Île-ŕ-la-Crosse, Sask. on Sept. 1, 1785. Her mother was Cree and her father, Patrick Small, was in charge of a North West Company trading post at Île-ŕ-la-Crosse. When Small was five, her father retired from the NWC and returned to England, leaving his wife and children behind.

Small met and married David Thompson, 29 at the time, at the age of 13.

With her knowledge of the fur trade and Aboriginal peoples, her ability to speak Cree, English and some French, her understanding of how to survive on the land and her connections in the fur trade as the daughter of Patrick Small, she played an integral but silent role in Thompson’s success as Canada’s pre-eminent explorer and mapmaker.

Shortly after their marriage, Thompson and Small travelled west and established a small fur trade post overlooking the North Saskatchewan River that would become known as Rocky Mountain House.

From that post, Thompson continued his westward exploration, making his first foray through the Rocky Mountains by way of Howse Pass.

Of that journey through Howse Pass in 1807, Thompson wrote: “The water descending in innumberable Rills, soon swelled our Brook to a Rivulet, with a Current foaming white, the Horses with Difficulty crossed & recrossed at every 2 or 300 yards, & the Men crossed by clinging to the Tails & Manes of the Horses, & yet ran no small danger of being swept away & drowned.”

What Thompson did not record in his journal, according to Rocky Mountain House historian Pat McDonald, is that Charlotte faced those same dangers and challenges with three children under her wing, including an infant carried on her back in a papoose.

This incident alone says much about Charlotte’s remarkable qualities, McDonald said. She could ride, hunt and canoe, and the Howse Pass trip was her first time in the mountains, as well.

“I was talking to a class of Grade 4s and I said one word, ‘Sacagawea,’ and the class knew who she was. They knew right away who she was. What I’m trying to say is that we don’t promote history enough,” McDonald said. “We don’t seem to be able to promote our own history. I hate to seem biased, but I don’t think we promote a lot of Western Canadian history either.

“With Charlotte, the history in those days was written by men and mostly about men and David Thompson hardly wrote about his wife.”

McDonald added that even when they were married all Thompson wrote was: “On this day wed Charlotte Small.”

Even if he rarely mentions her in his journals, McDonald said he did not take her for granted or treat her as a convenience, something many fur traders did with their “country wives,” often abandoning them and any children they might have had together, such as what Patrick Small did.

The story of Thompson and Small is altogether different; McDonald said that while it is filled with adventure, it is also a great Canadian love story.

“You test a good love story by how they handle the hard times and I think in this case by what they did and what they went through,” he said, adding despite all the hardship, the couple remained together, dying within three months of one another.

Thompson retired from the fur trade in 1812 and the couple, along with their children, left the West for Quebec. Two of the children, John and Emma (two of the three children who crossed Howse Pass), also died within three months of one another. In each case, Thompson himself made the coffin.

“They weren’t used to the food. They weren’t used to the living conditions,” McDonald said.

Thompson also lost all of his money through bad business dealings and failed ventures, eventually forcing the couple to rely on their children in their final years.

During their time in Eastern Canada, Small invariably stayed home when Thompson went out in the evening, an indication McDonald said of the racism of the time and yet one more challenge the indomitable Small would have had to endure.

According to McDonald, Small’s grandson William described Charlotte “as extremely reserved except with family and reflected that his granddad was a man who enjoyed simple home cooking and drank nothing but tea and milk, who always dressed plainly and had no use for style or fashion of any kind. Charlotte, however, made it her special business and pride to take care of his clothes, and always looked him over carefully before going out.”

On many other evenings, however, Small and Thompson would go out together holding hands to look at the stars and reminiscent about the West and their life together.

Small died in 1857 at the age of 71, three months after Thompson died. Both are buried in the Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal. Small’s grave is marked with a small plaque with “The Woman of the Paddle Song” inscribed upon it.