What difference does 100 metres make?

If you are a grizzly bear trying to make your way through one of the most densely developed valleys in the Canadian Rocky Mountains – it could mean the difference between survival and potential human conflict.

With Three Sisters Mountain Village submitting its final wildlife corridor alignment to the provincial government in the past couple of months, the discussion of what constitutes an effective corridor for wildlife movement has again resurfaced.

Hosting a recent community conversation on the issue, Stephan Legault, with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, and wildlife biologist Karsten Heuer both spoke on how critical the width of the corridor is in this context.

Heuer provided those who attended the presentation with an overview of scientific literature and research that speaks to wildlife movement – both slope and width of corridors, as well as what is referred to as the “zone of influence” for wildlife.

He said research has shown that across species, wildlife prefer to travel through a landscape that has a slope lower than 25 degrees. The minimum 450-metre width is critical, he said, to prevent adjacent human uses from disturbing wildlife as they move – the so-called zone of influence.

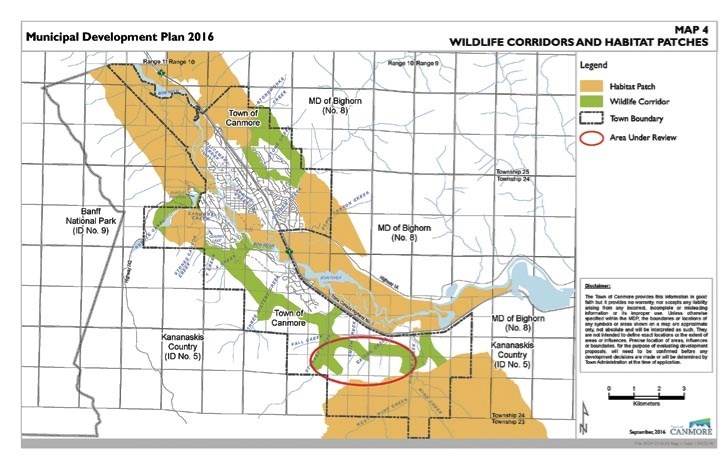

Both form part of requirements for wildlife corridor design in the Bow Corridor Ecosystem Advisory Group’s guidelines for wildlife corridors and habitat patches, which Heuer helped develop. The guidelines, however, do not apply to the proposed TSMV lands for development known as Smith Creek or sites seven, eight and nine.

“It has been a consistent message,” Heuer said regarding the 450-metre width and 25 degree slope. “It has been a message that current landowners who owned this property before 2008 and have definitely been engaged in the community would have been well aware of when they decided to purchase it out of receivership.

“These are tremendously successful business people and they do their research. This is not a surprise.”

The current proposal in front of Alberta Environment and Parks for consideration has a wildlife corridor width of 350 metres – 100 metres shy of the standard being sought by conservation groups.

“It is pretty darn close,” Heuer said. “It is basically 100 metres, so kudos to the developers … I think we have to recognize that involves private land and there is a cost to the developer.”

Alberta Environment was unable to provide a government official involved in the wildlife corridor decision-making process for an interview with the Outlook before press deadline.

Both Heuer and Legault encouraged the community to push for that extra 100 metres to provide more confidence in the future that wildlife will be able to effectively navigate through the valley from the Banff east gates to Kananaskis Country – an eight kilometre stretch on the northern side of the valley.

Legault said the Bow Valley is one of several locations throughout the 1.3 million square kilometre landmass recognized as the Yellowstone to Yukon region where future development is proposed and could affect movement of wildlife on a regional scale.

“The Bow Valley, it turns out, is one of a handful of key locations across the region where we know we must achieve success in order to have success at the entire continental scale of Yellowstone to Yukon,” he said.

Indeed, connectivity for wildlife through the Bow Valley fits into the larger vision of Y2Y, which is to see both people and nature thrive on the landscape. For wildlife to thrive and move around on the land, said Legault, there need to be spaces set aside that not only allow that to happen, but that connect with the larger region.

Y2Y works on collaborations with local groups throughout the broader region – which covers areas in two countries – and Legault said that work has been successful since the organization began in 1994. In that 25 years, he said, Y2Y has worked with 300 different organization, non profits, community groups, government, educational institutions and First Nations and seen an increase in protected land of 20 per cent.

“This is the model by which work gets done in the conservation world these days – through partnerships and collaboration,” Legault said. “Our vision is that 100 years from now, our great great grandchildren will be able to look upon this landscape and see it is protected and connected so that people and nature can thrive.”

Yellowstone to Yukon’s beginnings were predicated on the 1992 Natural Resource Conservation Board decision that granted TSMV development rights on the lands, regardless of whether the community or council opposed it.

As a result of that NRCB decision, the authority to designate wildlife corridors was granted to the provincial government, but the decision on how and where development should proceed is up to the Town of Canmore and its locally elected council.

Some of those who attended the community conversation, and are new to the community over the past decade, were confused as to why development is happening at all on the land if it is critical for wildlife movement.

Legault said with the final wildlife corridor to be decided in the Bow Valley soon, it will be the final test of the community’s commitment to getting connectivity right.

“The decisions we have made over and over again in Canmore and the Bow Valley have created a situation where this is the conversation we are having,” he said. “We are making some of the last decisions we are going to make about wildlife in the Bow Valley; it is beholden upon us to err on the side of caution.”

There are other changes being considered when it comes to that final wildlife corridor designation detailed by the developer. Those include the fact that because of the 2013 flooding of Three Sisters Creek, some areas of TSMV are no longer suitable for development.

The proposal being considered, according to QuantumPlace planner Jessica Karpat, is aligning the steep creek with the wildlife corridor and a second underpass under the Trans-Canada Highway.

During an online webinar hosted by QuantumPlace, which represents TSMV, the fact that two underpasses may be available to wildlife was considered a possible improvement to the cross-valley corridor.