David McMillan says he was just following his instincts when trying to make photographs that would succeed as art.

He thought landscape was more interesting, broadly speaking, and not just mountain pictures, even though he has photographed in Banff on a number of occasions.

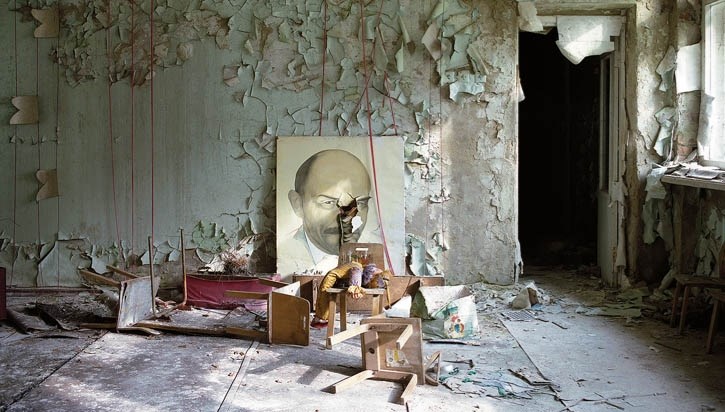

What he realized was how we as humans interacted with nature was really the subject he wanted to capture – our relationship to the natural world, how well we do it, or how poorly we do it.

McMillan’s instincts and art have led him on a 20-year odyssey, travelling to Ukraine to photograph the damage and effects left from the Chernobyl nuclear reactor meltdown of 1986. McMillan’s exhibit, Growth & Decay: 20 Years in Chernobyl, will take place Saturday (Feb. 20) at 7:30 p.m. in the Canmore Collegiate High School Theatre. Doors open at 7 p.m.

The accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant was the most severe in the history of the nuclear power industry, causing a huge release of radionuclides over large areas of Belarus, Ukraine and the Russian Federation.

The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) identified 49 immediate deaths from trauma, acute radiation poisoning, a helicopter crash and cases of thyroid cancer from an original group of about 6,000 cases of thyroid cancers in the affected area. Another U.N. study estimates the final total of premature deaths associated with the disaster will be around 4,000, mostly from an estimated three per cent increase in cancers, which are already common causes of death in the region.

“Luckily, I was teaching so I had an income to fall back on,” said McMillan. “Because I had a teaching job it was pretty ideal, I could be self-indulgent in as far as I could do work that maybe wouldn’t make any sense ... but made sense to me,” McMillan said. “I went eight years later in ’94 and it’s actually been 19 trips now.”

Since he had been photographing how awkward it seemed to him our integration is with nature, when he read an article in 1994 about the accident and the post-accident condition of the area known as the exclusion zone, it seemed like it would be something interesting to photograph.

“I was able through a number of phone calls, faxes and lucky connections to get permission to go and it turned out to be something that really clicked for me. It satisfied something in making photographs about a subject that I thought mattered and at the same time maybe satisfied something of my artistic impulse,” McMillan said.

Driven to the border where the guarded section begins, his driver had a conversation with the man who was in charge of the area.

“The interim person asked for some money, which I’m told was accepted by the person in Chernobyl and I was admitted, and from then on it was easy,” McMillan said. “I got to know people, and on my first few visits I donated pharmaceuticals which were in short supply; this was just for the people who worked there because everyone else had been evacuated.”

There were some places where he was told to just stay a few minutes because the radiation was high, but in only one place had to wear a mask; otherwise there were no restrictions, which surprised him. For the most part there were no limitations, which he appreciated because to capture the work you can’t just dash around in a 30-kilometre irradiated area.

“In fact, today anyone can go if they want to take a tour bus that actually drives around the area, so today it’s like going to Disneyland,” McMillan said. “It’s odd that people would want to go as tourists. I don’t know if my motives were any different, but I like to think they were. To go for just an afternoon to say you’ve seen it, I guess there’s a name for it – disaster tourism.”

Pripyat, Ukraine was the city where workers and their families lived and it was the biggest and most interesting for McMillan to shoot due to it being a fairly new city with schools and hospitals – somewhat like a western city with high-rises and not like the rustic villages scattering Ukraine with remnants of the Soviet culture.

“Nature is really interesting because it is reclaiming itself, and this year is actually the 30th anniversary of the accident. But even in my first visit eight years after the accident, I was surprised by the growth of trees ... it just seemed to happen quickly,” McMillan said.

“I never expected to go back, but I felt after the first visit that I hadn’t seen everything, there was still more to see, so I kept going back with an interest to see what had changed, to re-photograph places that I had already visited and the change.”

He was shown pine trees that were grown with seeds that were irradiated, and it was pointed out to him that the needles were somewhat corkscrewed, with a lot of excess cone production.

“I even met the person in charge of forestry for the area, and he said it seemed radiation had stimulated growth in trees, but it wasn’t the case, and I haven’t seen any animals that look any different,” McMillan said.

The area is also now a wildlife preserve, with no hunting permitted, with animals along with foliage repopulating and reclaiming the area. Another obvious reason behind the preserve is not wanting people eating irradiated animals.

Will there be another trip to the site?

“There’s a couple of things I’m curious to see. They’re building a huge covering for the reactor, less than a kilometre from, it and they’re going to slide it over, like a huge, curved stadium almost. It’s more than two city blocks long and I thought that might be something to conclude the series,” McMillan said.

“Right after the accident they built a concrete and steel covering and it’s riddled with leaks and cracks all over the place and just not going to last, and because the reactor’s core is exposed, it would still allow too much radiation into the atmosphere.

“Economically, Ukraine is in rough shape, the currency is deeply undervalued. I think that’s the overwhelming concern; the accident is just a bad memory like, say, World War II or something, and once again facing Russian aggression – it’s been a rough ride for them, so the Chernobyl business is insignificant, I think, compared to what they really have to worry about these days.”